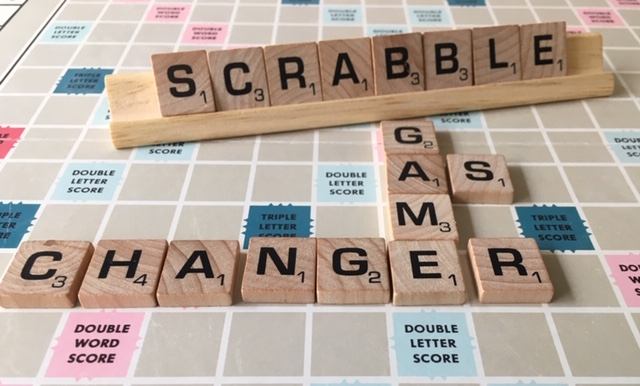

In October, after I read Jonathan Kay’s Wall Street Journal review “Scrabble is a Lousy Game,” I meditated on his criticism of Scrabble as a word game that deemphasizes semantics. I asked myself, if I want my students to play a board game that cultivates word power and critical thinking skills, is Scrabble the game to choose? Thus, Kay’s review became the starting point for my research on the cognitive benefits of Scrabble play. As I scrolled through search results, I found only a couple of articles that specifically addressed Scrabble in the college classroom, but many that focused on the value of the game, itself, for sharpening the mind.

The dearth of articles on Scrabble in the college classroom may be explained by the emphasis on classwork with assessable outcomes rather than activities that foster the habits of mind essential to lifelong learning. The bibliography that follows includes Kay’s review, the starting point for my research, along with three refereed research articles. Two offer windows into the classrooms of professors whose students play Scrabble: one an English professor at a two-year college in California, the other a professor of engineering at a polytechnic university in Russia. The third article addresses cognitive evaluations of competitive Scrabble players and what they reveal about how experience shapes word recognition.

How much does Scrabble play cultivate our word power? The answer to that question remains unclear, but the research of psychologists and educators points to the merits of team Scrabble for improving not only our language skills, but also our facility with critical thinking, team-building, and spatial skills.

As I review my research on Scrabble, I look forward to searching for additional studies and commentary on the game. Whether it will lead to a larger project of my own, I do not know. But the knowledge I have gained will inform my teaching as I continue to revise the curriculum and consider additional opportunities for wordplay in the classroom.

Annotated Bibliography

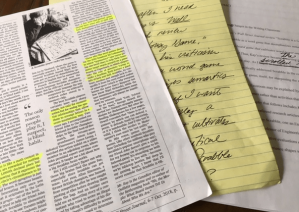

Fletcher, Jennifer. “Critical Habits of Mind: Exposing the Process of Development.” Liberal Education, Winter 2013, pp. 50-55. Association of American Colleges and Universities, https://www.aacu.org/publications-research/periodicals/critical-habits-mind-exposing-process-development. Accessed 26 Nov. 2018.

“Critical Habits of Mind” addresses the teaching practices of a group of college math and writing faculty who collaborated to develop lessons to foster intellectual capacities, such as motivation and self-efficacy. Developmental educational instructors from three California colleges, Cabrillo, California State University-Monterey Bay, and Hartnell College, partnered to pilot classroom activities, including clicker technology, peer writing review, improvisation, metacognitive writing activities (e.g. “Math Anxiety Essays”), and Scrabble Fridays. Reflecting on their collaboration, author Jennifer Fletcher, associate professor of English at CSUMB, observes that foregrounding procedural knowledge, as their pilot activities did, enabled them to couple their teaching of discipline-specific content with the set of behaviors essential to teaching and learning.

Fletcher’s account of Hartnell writing instructor Hetty Yelland’s Scrabble Fridays is of particular value to educators who are considering Scrabble play as a classroom activity. Fletcher notes that Yelland’s observes “the extra effort students have to make to overcome the boredom—and their passive word knowledge—that eventually leads to more active and internalized language practices” (54).

Hargreaves, Ian S., et al. “How a Hobby Can Shape Cognition: Visual Word Recognition in Competitive Scrabble Players.” Memory & Cognition, vol. 40, no. 1, 2012, pp. 1-7. ProQuest, http://nclive.org/cgi-bin/nclsm?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/952889499?accountid=9935.

“How a Hobby Can Shape Cognition” presents the findings of Canadian researchers in the Departments of Psychology and Medicine at Calgary University who investigated how the word recognition skills of competitive Scrabble players differed from those of age-matched nonexperts. The researchers’ cognitive evaluations revealed differences only in Scrabble-specific skills, such as anagramming. Also, the researchers observed that Scrabble expertise was associated with two specific effects: vertical fluency and semantic deemphasis. The study’s results indicate that experience shapes visual word recognition.

The research of Ian Hargreaves and his colleagues at the University of Calgary is pertinent to educators who seek to understand the cognitive benefits of frequent Scrabble play. Notably, the semantic deemphasis that the study identifies—and that Jonathan Kay addresses in his review—contrasts the gains in language skills that Hetty Yelland observes in her English students.

Kay, Jonathan. Review. “Scrabble is a Lousy Game.” The Wall Street Journal, 6-7 Oct. p. C. 5.

In “Scrabble is a Lousy Game,” writer and editor Jonathan Kay criticizes Scrabble for its lack of emphasis on semantics. In Kay’s words, the game “is like a math contest in which you are rewarded for reciting pi to the 1,000th decimal place but not knowing that it expresses the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter” (C5). Kay asserts that the best board games for casual players involve a mix of luck and skill and recommends two other board games, Codenames and Paperback, as better options for wordplay.

While Kay’s review focuses on the competitive player’s approach to Scrabble, the concerns he raises about the game’s deemphasis of word meaning and the frustration that novice players can experience warrant the attention of educators who are considering introducing Scrabble play into their classrooms. And his recommendations of Codenames and Paperback offer teachers two word-game options to pursue as alternatives Scrabble.

Kobzeva, Nadezda. “Scrabble as a Tool for Engineering Students’ Critical Thinking Skills and Development.” Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, no. 182, 2015, pp. 369-74. ScienceDirect, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877042815030669. Accessed 26 Nov. 2018.

“Scrabble as a Tool for Engineering Students’ Critical Thinking Skills and Development” presents research involving second-year engineering students and teachers of EFL (English as a Foreign Language) at Tomsk Polytechnic University in Tomsk, Russia. The students—all non-native speakers of English—played Scrabble as an in-class and out-of-class-activity for one academic year. At the end of the year, the best six student players competed in teams in a tournament against two teams of the six EFL teachers. Throughout the tournament—which was conducted outside of the classroom to relieve students of the pressure to obtain a high score—the researcher, Nadezda Kobzeva, observed the contrast in the students’ and teachers’ practices as players. While the EFL instructors possessed an advanced knowledge of English language, they were newcomers to Scrabble. On the other hand, the engineering students with limited knowledge of English relied on the skills they developed throughout their year-long Scrabble program. In the feedback the students provided after the tournament, which they won, the majority of students rated the skills they developed as Scrabble players as excellent in all five fields assessed, including team-building, thinking, spatial skills, vocabulary, and spelling.

Kobzeva, a professor of engineering at Tomsk, focused his research on engineering students, but his findings are valuable to researchers and teachers in other fields who seek answers to the questions of how Scrabble can be used effectively as a learning tool, and what specific skills students may develop through frequent play.

In Zadie Smith’s novel Swing Time, the narrator recalls how she and her childhood friend Tracey watched snippets of Top Hat over and over to study Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers’ dance routine for “Cheek to Cheek.” Recounting Tracey’s knack for forward-winding the video tape to the exact moment she sought, the narrator observes that “she [Tracey] began to read the dance, as I never could, she saw everything” (56). As I read those words, I realized that Tracey’s attention to detail and her ability to see “the lesson within the performance” (56), was the same practice of close study that I require of myself and my students.

In Zadie Smith’s novel Swing Time, the narrator recalls how she and her childhood friend Tracey watched snippets of Top Hat over and over to study Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers’ dance routine for “Cheek to Cheek.” Recounting Tracey’s knack for forward-winding the video tape to the exact moment she sought, the narrator observes that “she [Tracey] began to read the dance, as I never could, she saw everything” (56). As I read those words, I realized that Tracey’s attention to detail and her ability to see “the lesson within the performance” (56), was the same practice of close study that I require of myself and my students. Designing a course that dovetails with campus cultural events not only means crafting new assignments every semester but also reading some books that I might not choose to read—much less teach—on my own. While those challenges could dissuade me from starting anew each semester, repeatedly reinventing English 131 has proven to have lasting benefits. Books whose authors we can see face to face when they visit campus and plays that come to life on the university stage give the course an immediacy it would not have otherwise. And though I cannot fully place myself in the role of my students, I can at least come closer to that by giving myself the task of studying different texts, as they do, every semester. As a writer, I avoid the cliché comfort zone, but as a teacher, I embrace the concept. I try not to get too comfortable. I allow myself to stumble, as Erik Larson, author of The Devil in the White City, would say.

Designing a course that dovetails with campus cultural events not only means crafting new assignments every semester but also reading some books that I might not choose to read—much less teach—on my own. While those challenges could dissuade me from starting anew each semester, repeatedly reinventing English 131 has proven to have lasting benefits. Books whose authors we can see face to face when they visit campus and plays that come to life on the university stage give the course an immediacy it would not have otherwise. And though I cannot fully place myself in the role of my students, I can at least come closer to that by giving myself the task of studying different texts, as they do, every semester. As a writer, I avoid the cliché comfort zone, but as a teacher, I embrace the concept. I try not to get too comfortable. I allow myself to stumble, as Erik Larson, author of The Devil in the White City, would say.