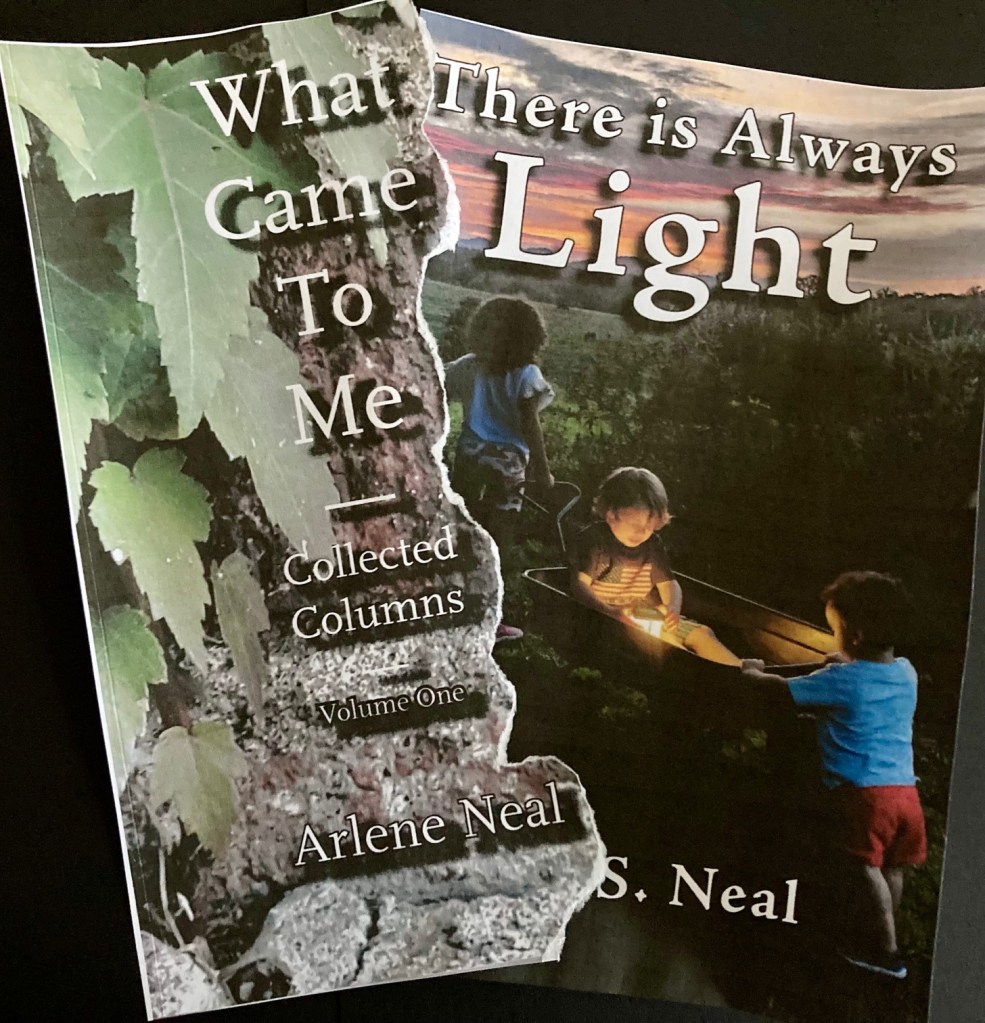

When an author follows a collection of personal essays, or columns, with one of autobiographical poetry, or vice versa, she leads readers of both volumes to consider how she depicts some of the same people and themes in a different genre. Such was the case with Arlene Neal’s book of poems There is Always Light (2023), the follow-up to her first book, What Came to Me (2020), a collection of her weekly columns from The News-Topic.

The poem “God help me not to hate” echoes the column “New Shoes and Self Esteem,” in which a thoughtless classmate observes that the writer’s loafers are “not Bass Weejuns” (48). The girl who speaks those words could easily be one of the girls who “wear / pink pearl nail polish and wear / pleated skirts and new shoes” (lines 4-6). But those girls in the Sunday school class are not the antagonists of the poem; rather, it’s the Sunday school teacher, herself, who treats the speaker of the poem as an object of scorn. The speaker—what we call the narrator of a poem—does not actually speak. She refrains from answering the teacher’s questions, sitting, in her words, “on both hands / so she [the teacher] won’t see my black nails / and fingers stained yellow / from working in tobacco” (lines 7-10).

That girl who hides her tobacco-stained fingers is the girl on the bus in “New Shoes . . . ,” but the silent speaker of the poem is not the adult retrospective narrator of the column. At the end of the poem, she still sits in Sunday school, while the girl who was humiliated on the bus has grown up “to understand the value of [her] personhood” (48). Yet even though the speaker in the poem lacks the adult perspective of the writer of “New Shoes . . . ,” she gains insight—not from the lesson that the teacher attempts to impart but from her own epiphany: her recognition of the teacher’s hypocrisy.

Just as “God teach me not to hate” recollects “New Shoes and Self Esteem,” “A Baseball Poem,” “End of the Season,” and “World Series 1966” all recall the column “The Longest Game and Life Lessons.” The baseball-playing father and daughter of the column figure in all three poems, but it isn’t the bat and ball of “The Longest Game,” the first half of the column’s title, but instead the “Life Lessons” of the latter half of the title that resonate in the trilogy. At the end of the third poem, the speaker notes, “I really / cannot remember what the movie / was about, or who won that game” (38-40). She doesn’t remember because the events unfolding on the TV screen that her father watches intermittently and the action on the drive-in movie screen that her date aggressively prevents her from watching are not what she has carried with her from that night—and subsequently brought to the poem.

In a sense, the destination of none of the three baseball poems is the ballpark: the first leads us to post-traumatic stress disorder; the second, to the twilight of childhood; the third, to unwanted sexual advances. As the writer notes in “A Baseball Poem,” “To write baseball poems / is really the yearning to see” (lines 1-2). The products of Arlene Neal’s “yearning to see” shine through the lines of her poems and the sentences of her columns. This reader hopes—as do others, I’m sure—that more volumes of her poetry and columns will follow.

Works Cited

Neal, Arlene. There is Always Light. Redhawk Publications, 2023.

—. What Came to Me. Third Lung Press, 2020.