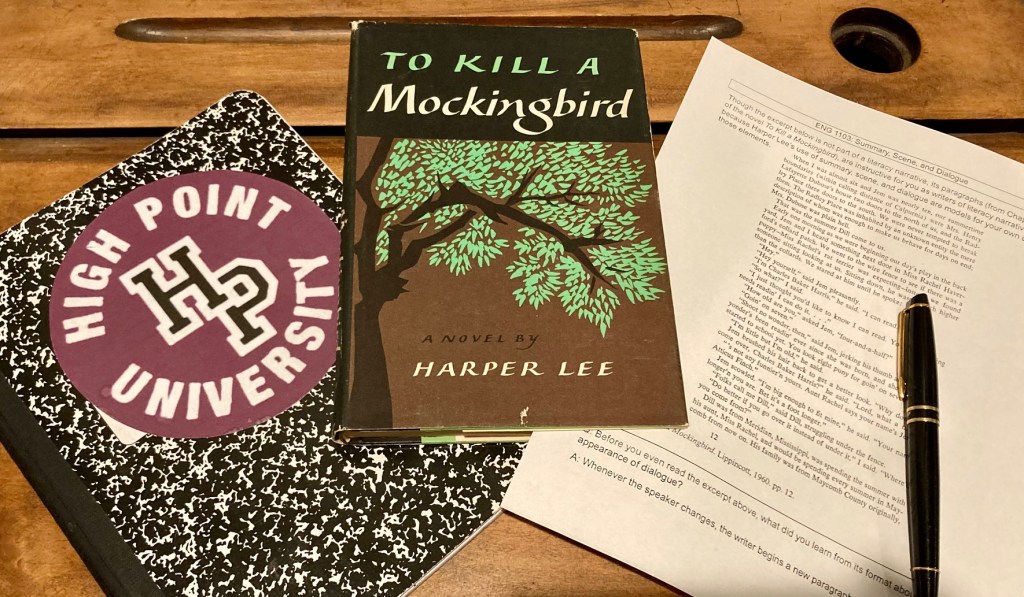

Yesterday before you and your group members assessed the literacy narratives that you read for class, we examined a page (pictured above) from Harper Lee’s novel To Kill a Mockingbird. That page from Chapter One serves as a useful model for three narrative elements: summary, scene, and dialogue–at least two of which will figure in your literacy narrative.

The first paragraph of the passage sets the scene with summary, designating the “summertime boundaries” within which the narrator, Jean Louise, “Scout,” Finch, and her older brother, Jem, may play outdoors (12). The short one-sentence paragraph that follows continues the summary, informing readers that the summer Scout has just summarized is the one in which Dill (Charles Baker Harris) first visits Maycomb, Alabama.

With the first words of the next paragraph, “[e]arly one morning,” Scout shifts from summary to scene (12). All of the remaining paragraphs except the final one continue the scene with dialogue. Scout returns to summary with the words “Dill was from Meridian” (12).

Note that Harper Lee begins a new paragraph whenever the speaker changes. Also note that every line of dialogue does not include a dialogue tag, such as “he said” or “she said.” If a passage of dialogue includes only two speakers, none of the paragraphs require dialogue tags after the speakers’ first lines because the start of a new paragraph signals to the reader that the other person is speaking. If a dialogue includes three or more speakers–such as Scout’s conversation with Jem and Dill–occasional tags are essential.

In my notes above, I have been careful to distinguish between the author, Harper Lee, and the narrator, the fictional character Scout. When you write about an autobiographical work, such as a literacy narrative, you may use the terms writer and narrator interchangeably. When you write about a work of fiction, it’s important to separate the narrative voice from the author. Reserve the term author for published writers. When you write about a piece of student writing, refer to the student as a writer, not an author.

Sample Student Literacy Narratives

The paragraphs that follow include detailed but not comprehensive notes on the two sample narratives that you assessed in class yesterday. Look to these notes as a guide for editing your own literacy narrative.

“Creativity is Key”

- The writer changes the font of the body of the paper to Times New Roman but does not change the font of the running header, which should also be Times New Roman.

- The writer incorrectly adds an extra space between the first-page course information (in the upper left) and between the title and the first line of the essay. MLA-style manuscripts are double-spaced. Note that later, the writer also incorrectly adds space between the paragraphs.

- The title should be typed in twelve-point font, which is the font size that should be used throughout the document.

- The title should not appear in boldface.

- In MLA style, all major words in a title, including the final one, are capitalized (“key” should be “Key).

- Form, which is the focus of the previous notes, is less important than content, but easily avoidable errors of form may prevent a reader from appreciating the content of your narrative. Creating a compelling story is hard work, proofreading isn’t. If you don’t get the easy part right, readers may stop reading.

- The second “sentence” of the second paragraph is a fragment because the meaning of “one being my senior year . . .” is dependent upon the clause that ends the previous sentence. See Writing Analytically, page 426-29.

- The comma between “all” and “matter” is a comma splice. See Writing Analytically, 429.

- “[R]eal life” should be hyphenated (as real-life) when it functions as a compound modifier. Ditto for “open minded” and “four to five.”

- Errors of letter case–upper rather than lower, or vice versa–are mistakes of mechanics, which are prevalent in the second paragraph “Track, “Field,” “Defensive,” “Back,” and “Athlete” should all began with a lower-case letter.

- “[F]elt like” should be “felt as if.” In comparisons, use “like” before a noun and “as if” before a clause.

- “I’m a writer that” should be “I’m a writer who.” The correct relative pronoun for a person is “who,” not “that.”

- The essay is not a narrative. The writer mentions his experience writing a Southern gothic story, and he briefly recounts writing about his training for track and field and international football (soccer), but the writer offers very few details. Focusing on one of those experiences and recreating one or more moments from it would transform the essay into a narrative and develop it into one that meets the six hundred-word minimum requirement.

“Giving a Speech: Worst Nightmare to Best Feeling”

- In the second line of the second paragraph, “Megan” is a parenthetical element that should be set off by commas. See Writing Analytically, 441.

- The parenthetical element is the next line, “Mrs. Hron’s,” is correctly set off with commas, but the word that precedes “Mrs. Hron’s” should be possessive (“teacher’s,” not “teachers”).

- Several other minor punctuation errors occur in the essay, but overall it’s a strong literacy narrative that’s notable for its vivid scenes and the writer’s self-deprecating humor.

Notes on Monday’s Quiz

Rather than posting the answers to the quiz, I am asking you to review the sample student literacy narratives, my annotations on your assignments, and the class notes for January 28 and February 3 and to find the answers on your own. Doing so will enable you to retain more of the course content from the past two weeks of class.

Keep in mind that one of the reasons we write is to remember. Taking notes on all of the blog entries that I publish and on all of your other reading assignments will both engage you in learning process and enable you to demonstrate your learning in the course.

Integrating Quotations

Writing your reflective essay on your literacy narrative tomorrow will include an exercise in integrating a quotation into your writing, a practice you will engage in more frequently as the semester progresses.

In your reflection, you are required include a minimum of one relevant quotation from the textbook, Writing Analytically, which you will introduce with a signal phrase and follow with a parenthetical citation.

Examples

The authors of Writing Analytically observe that “[o]ne goal of a writer’s notebook is to teach yourself through repeated practice that you are capable of finding things to write about” (Rosenwasser and Stephen 157).

In Writing Analytically, Rosenwasser and Stephen note, “to a significant extent, writing of all kinds tells a story—the story of how we have come to understand something” (162).

In the first example above, the authors’ last names appear in the parenthetical citation because they are not named in the signal phrase. In the second example, only the page number appears in the parenthetical citation because the authors are named in the signal phrase.

At the end of your essay, you will include a work cited entry for the section of the textbook that you quote.

Sample Work Cited Entries

Rosenwasser, David and Jill Stephen. “On Keeping a Writer’s Notebook.” Writing Analytically, 9th edition. Wadsworth/Cengage, 2024. pp. 157-58.

Rosenwasser, David and Jill Stephen. “Writing from Life: The Personal Essay.” Writing Analytically, 9th edition. Wadsworth/Cengage, 2024. pp. 161-63.

Next Up

In class tomorrow, you will compose a short essay that reflects on the processes of planning, drafting and composing your literacy narrative. If you do not post your essay to Blackboard and WordPress before class (you have until Friday morning to do so), you should refer to your work as ongoing. Be sure to bring your copy of Writing Analytically to class.