or “We’re Going to Need a . . .”

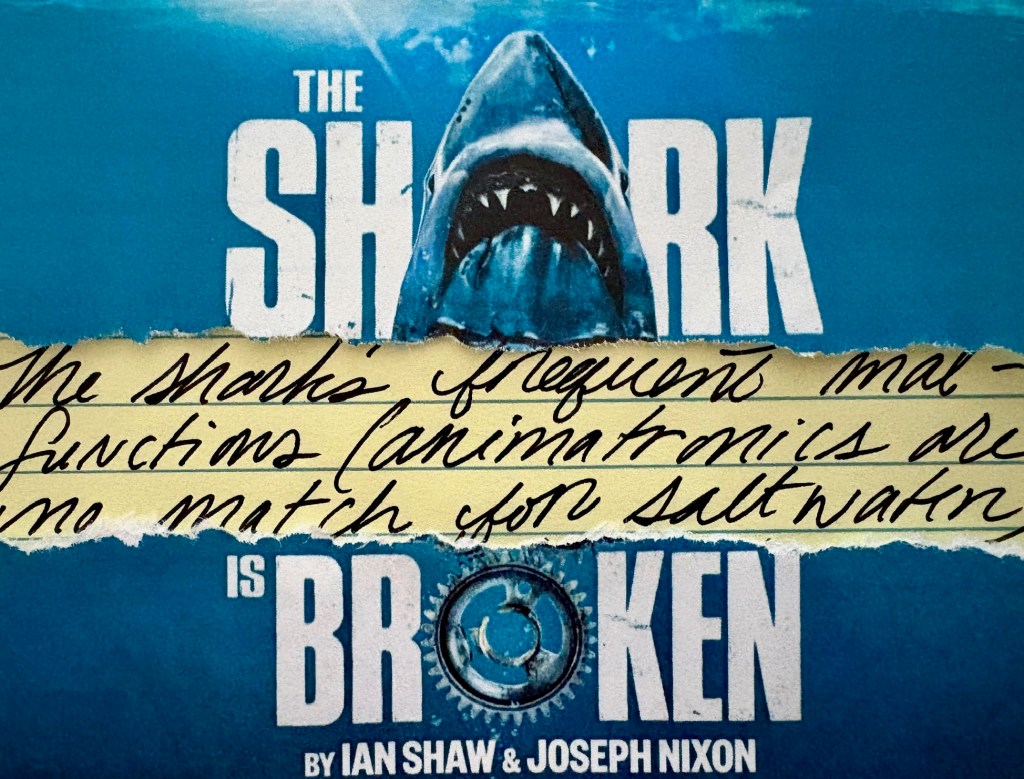

On August 16, 17, and 23, audiences at the Winston-Salem Theatre Alliance’s Beall black box theatre found themselves aboard the Orca with Robert Shaw (Patrick Daley), Richard Dreyfuss (Kenan Stewart), and Roy Scheider (Robert Evans), waiting for the tech crew to repair the mechanical shark for the umpteenth time. The shark’s frequent malfunctions (animatronics are no match for saltwater)—a staple of behind-the-scenes accounts of Jaws—try the actors’ patience, none more so than Shaw’s. Like his character in the film, the eccentric shark hunter, Quint, Shaw is a quick-tempered alcoholic. His similarities to his character prompt Dreyfuss to remark that he isn’t sure where Shaw ends and Quint begins. Shaw exploits that blurred line, needling the neurotic Dreyfuss who hops about the Orca’s deck like a nervous rabbit, confessing his desire to meet the renowned playwright Harold Pinter.

Shaw, a masterful interpreter of Pinter’s work, cruelly misleads the naïve Dreyfuss, telling him that Pinter would love for Dreyfuss to call him in the morning and tell the playwright his own interpretations of his plays. When Shaw and Dreyfuss almost come to blows—as they do more than once—it’s Scheider who serves as mediator, his primary function in the play. Like his Jaws character, Police Chief Brody, he’s there to keep the peace. Neither Brody nor Dreyfuss is as deftly drawn as Shaw, undoubtedly because one of the play’s coauthors, Ian Shaw, began the project that became The Shark is Broken as a way of exploring the life of his father, who died three years after he brought Quint to life on screen. Ian was only nine years old.

Like his father, Ian became an actor, and like his father, he turned to writing, but the two pursuits do not compete for the younger Shaw’s attention as they did for his father’s. In The Shark is Broken, Shaw—recipient of the Hawthornden Prize for his second novel—laments that he has neglected his writing in favor of a Hollywood career, a choice he makes not for stardom but to support a family of (then) nine children. When Shaw recites Shakespeare’s Sonnet 29, his utterance of the desire for “this man’s art and that man’s scope” (7) speaks to his longing to write. Notably, he recites the sonnet as an antidote to Dreyfuss’ panic attack. Though Shaw has bullied the younger actor throughout the play, when Dreyfuss finds himself in crisis, Shaw speaks the words that calm him.

Shaw’s own writing comes to the fore in two scenes that depict his signature monologue, the speech that recounts the horrific aftermath of the torpedoing of the U.S.S. Indianapolis after it delivered the atomic bomb to the island of Tinian. Many of the sailors who survived the ship’s attack by the Japanese were later ripped to pieces by sharks. In the film, the monologue traces Quint’s deep-seated hatred of sharks to its depths in the Western Pacific, where hundreds of his shipmates perished in a sea of blood. In the play, the monologue foregrounds Shaw’s own writing. Rehearsing the scene, Shaw balks at the screenwriters’ shoddy speech. Then, in frustration, he pens his own version, the one we have watched over and over as Hooper and Brody listen in awe.

The final scene of the play returns to the monologue, giving the audience a live performance of the lines they have watched Shaw utter countless times on screen, and the ones they have now watched the actor put on paper. I can hardly fathom the mega-meta quality of watching Ian Shaw in the first productions of The Shark is Broken—the younger Shaw performing the role of his father in a play that he, the son, cowrote, with Joseph Nixon, to depict his father portraying Quint . . . At a community theatre, the effect isn’t mega-meta, but it’s multi-layered, nevertheless. Audiences at Winston-Salem Theatre Alliance watched Triad actors Patrick Daley (Shaw), Kenan Stewart (Dreyfuss), and Robert Evans (Scheider) portraying Hollywood actors performing—or mostly waiting to perform—now-iconic roles. Call it a Chinese box or a hall of funhouse mirrors. Maybe we’re going to need a bigger metaphor.

Work Cited

Shakespeare, William. “Sonnet 29: ‘When, in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes.'” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45090/sonnet-29-when-in-disgrace-with-fortune-and-mens-eyes.