This morning I will return your drafts, and you will have the remainder of the class period to begin revising your literacy narratives on your laptops. You will have an additional week to continue your revision work before you submit the assignment to Blackboard and publish it as a WordPress blog entry. The due date is next Wednesday, September 10 (before class). The hard deadline is Friday, September 12 (before class). Directions for submitting your literacy narrative are included on your assignment sheet and on the Blackboard submission site. Next Monday, September 8, I will guide you through the submission processes step by step.

As you continue to revise your literacy narrative, consider visiting the Writing Center. If you do so, you will earn five bonus points for the assignment.

To schedule an appointment, visit the Writing Center’s sign-up page, email the Writing Center’s director, Professor Justin Cook, at jcook3@highpoint.edu, or scan the QR code above. To earn bonus points for your literacy narrative, consult with a Writing Center tutor no later than Thursday, September 11.

I attached a Writing Notes handout to your introductory reflective writing exercises, one that I noted you should keep in your pocket portfolio and refer to when you are composing assignments. I have included an additional copy of that list below, followed by a second list of notes, which I have attached to the drafts of your literacy narratives.

Writing Notes

- &: Do not use an ampersand (&) in place of the word and in formal writing.

- Abbreviations should often be avoided in formal writing. Do not write vocab for vocabulary. On first reference, spell out Advanced Placement in the name of a course. In subsequent references, AP is acceptable.

- A lot: Don’t use a lot a lot. There are a lot of better ways to express that idea, such as many, often, considerable, etc. If you use a lot in your writing, I will mark it with a d, which denotes diction or word choice.

- Compound modifiers are linked with a hyphen. Write twelve-page paper, not twelve page paper.

- English and the names of other languages are always capitalized. If you write English with a lower-case e, I will underscore the letter with three vertical lines. Those three lines are the proofreader’s mark that denotes the need for a capital letter.

- Hopefully: I hope is a more direct expression of your wish and is preferrable in formal writing.

- Numbers that can be expressed as one or two words are written as words, not figures, in MLA style, which is the style used in English courses as well as some other courses in the humanities. Write twenty-five, not 25.

- Paragraphs: Business writing calls for block paragraphs, but your writing for English 1103 and many of your other classes will require you to indent the first lines of each paragraph five spaces or one-half inch.

- Passive voice should often be avoided in formal writing. The subject should perform the action. Write we read several nineteenth-century novels, not several nineteenth-century novels were read.

- Then/Than: Than is used in comparisons; then refers to a point in time.

- Titles: In MLA style, the titles of book-length works are italicized. If you are writing longhand, the titles of book-length works are underlined. The titles of shorter works—such as essays, short stories, and poems—are enclosed in quotation marks.

Writing Notes, Part II

- Apart: If you write apart when you mean a part, you have the written the opposite of what you intended. Apart is separate from; a part is a segment of a whole.

- Appositive: an appositive phrase offers additional information about a word or phrase that precedes it. Consider this sentence: My journal, a worn, spiral-bound notebook with Snoopy on the cover, is near at hand most hours of the day. The words a worn, spiral-bound notebook with Snoopy on the cover are an appositive because they offer more information about the journal.

- Center: The preposition that follows the verb center is on, not around. Centering around is impossible. Try to do it.

- Commas are not the equivalent of periods. Consider the following pairs of independent clauses: (a) The test consisted of fifty questions. I thought it would never end. (b) The test consisted of fifty questions; I thought it would never end. (c) The test consisted of fifty questions, and I thought it would never end. A comma can join two independent clauses—as it does in example c—only if it is followed by a coordinating conjunction (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so, referred to as the acronym FANBOY). If you use a comma between two independent clauses without following it with a coordinating conjunction, you have created a comma splice.

- Do: What specifically did you? (There is almost always a stronger verb than do.) Drafted, revised, edited, reviewed, studied, and memorized are all verbs that denote a particular action. Use action verbs whenever possible.

- Modifiers: Place modifiers and modifying phrases as close as possible to the words they are meant to describe. Consider this sentence: As a four-year-old, my grandmother taught me to print the letters of the alphabet. In it, the person who is four is the grandmother, which makes no sense. (She cannot be a grandmother at four.) The sentence should be revised to read something like this: As a four-year-old, I learned from my grandmother how to print the letters of the alphabet.

- That/Who: The relative pronoun who, not that, refers to people. (That refers to things.) Do not write He is the teacher that taught me to how to develop my writing. Instead, write He is the teacher who taught me to how to develop my writing.

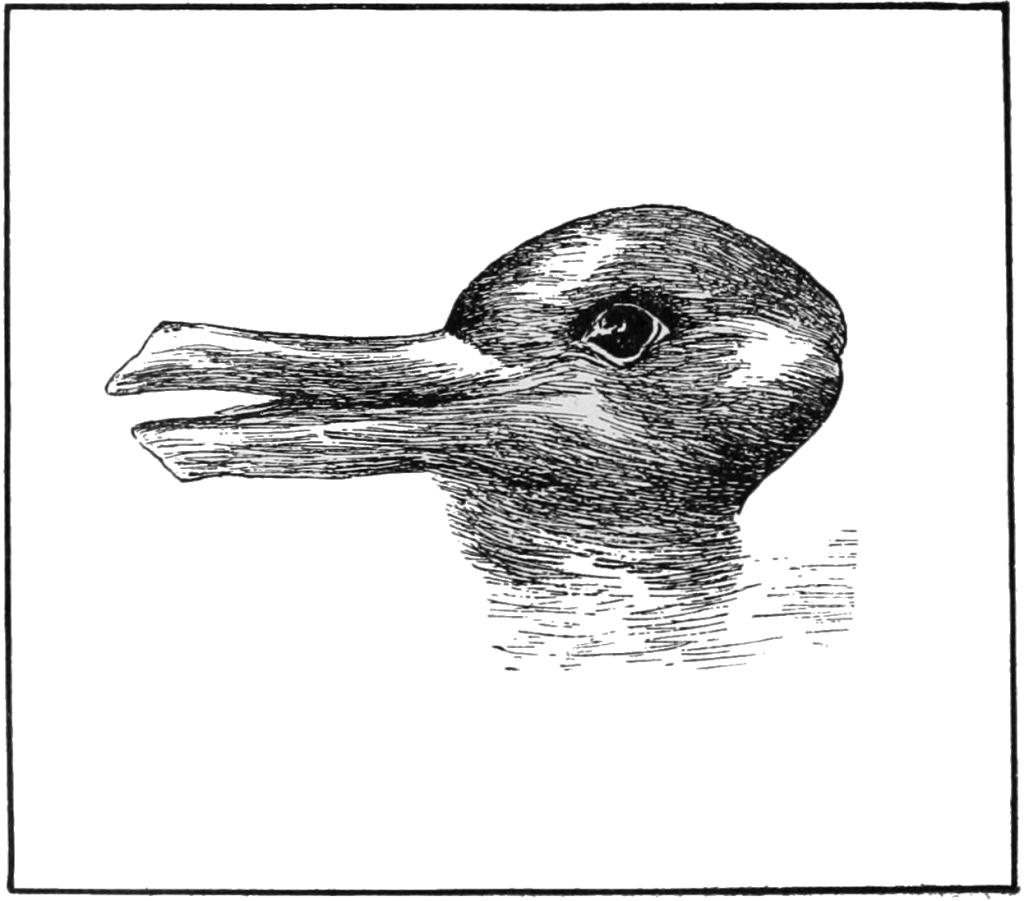

No Duck-Rabbit Illusion* Here

Monday at 7 a.m., after I parked my car, I spotted the duck and rabbit in the picture above. It’s not unusual to see a rabbit on campus in the early-morning hours or a duck swimming in the reservoir of one of the fountains. But Hayworth Hall is nowhere near any of HPU’s water features. Seeing those two creatures so close to each other was a lovely surprise. If you haven’t seen a duck or a rabbit on campus, take an early-morning walk.

*The duck-rabbit illusion theory demonstrates how a single image can be perceived in two distinctly different ways, underscoring the ambiguity of perception. Do you see a duck or a rabbit in the image below?

Next Up

Wordplay Day! To prepare for class, revisit the Dictionary and World Builder pages on the Scrabble website or the Merriam-Webster Scrabble Word Finder Page, and review the blog posts devoted to Scrabble.