Today we will examine an excerpt from the magazine article “The Falling Man,” by Tom Junod, which I will distribute at the beginning of class. Afterward, you will compose a short reflective essay focusing on the process of planning, drafting, and revising your literacy narrative. If you are still in the process of completing your essay (since you have until Friday morning’s hard deadline to post it), your reflection will address your work in progress. Instructions for your reflective essay are included below.

Directions: Compose a short reflective essay that documents the processes of planning, drafting, and revising your literacy narrative. Questions to consider include the ones listed on the back of this handout. You don’t need to address all the questions. Focus on the ones whose answers reveal the most about your work.

Include in your reflection a minimum of one relevant quotation from the textbook, Writing Analytically, from the section “On Keeping a Writer’s Notebook” or from “Writing from Life: The Personal Essay.” Introduce your quotation with a signal phrase and follow it with a parenthetical citation. At the end of your essay, include the heading “Work Cited,” followed by your work cited entry. (See the models on the below.)

Remember that the writing that follows the quotation should demonstrate its relevance. Although you are required to include a quotation, its presence in your writing shouldn’t seem obligatory. In other words, the quotation shouldn’t appear to be there simply because you were required to include it.

Example: When I began planning my literacy narrative, I was skeptical of the assertion that “the more you write, the more you’ll find yourself noticing, and thus the more you’ll have to say” (Rosenwasser and Stephen 157). However, as I wrote in my notebook about the difficulty of holding a page of newspaper when I was a preschooler, I once again saw how those long, thin sheets of newsprint would drape over me. Then I saw my parents holding their pages of newspaper with ease, and I was back in the den with them—where I was more than fifty years ago—marveling at their ability to read.

A variation on the previous option is integrating a quotation that serves as an epigraph in Writing Analytically. If you quote an epigraph, which is a quote at the beginning of a book or book section, intended to suggest its theme, you are presenting an indirect quotation.

Example: In The Situation and the Story, memoirist Vivian Gornick observes: “What happened to the writer is not what matters; what matters is the large sense that the writer is able to make of what happened” (qtd. in Rosenwasser and Stephen). That notion of what matters became apparent to me as I drafted the conclusion of my essay. The story itself is not dramatic but the bridge it delineates—the one that connects my preliterate self to my reading self—signifies a vital crossing point in my life.

The words that I quote are Vivian Gornick’s, but the source is the textbook Writing Analytically. That is why the parenthetical citation begins with qtd. in, to indicate that the words are quoted in David Rosenwasser and Jill Stephen’s book.

Note that when I introduce Gornick’s words, I use present tense because MLA style requires present tense in writing about written texts, whether fiction or nonfiction, mainstream or academic.

Sample Works Cited Entries

Rosenwasser, David and Jill Stephen. “On Keeping a Writer’s Notebook.” Writing Analytically, 9th edition. Wadsworth/Cengage, 2024. pp. 157-58.

Rosenwasser, David and Jill Stephen. “Writing from Life: The Personal Essay.” Writing Analytically, 9th edition. Wadsworth/Cengage, 2024. pp. 161-65.

Questions to Consider

You don’t need to address all the questions that follow. Focus on the ones whose answers reveal the most about your work.

- When you began transferring the words from your handwritten draft onto the screen of your laptop or tablet, what did you observe about the process?

- What aspect of the writing seemed the most challenging? Determining the focus of your narrative? Developing the story? Beginning a scene? Introducing dialogue? Crafting the conclusion? Why did that aspect of the writing seem the most challenging?

- Did you change the subject of your narrative? If so, what was the original subject? What did you change it to? Why?

- Did you change the organization of the narrative? For example, did you initially present the story chronologically, then begin in the present and move to flashback?

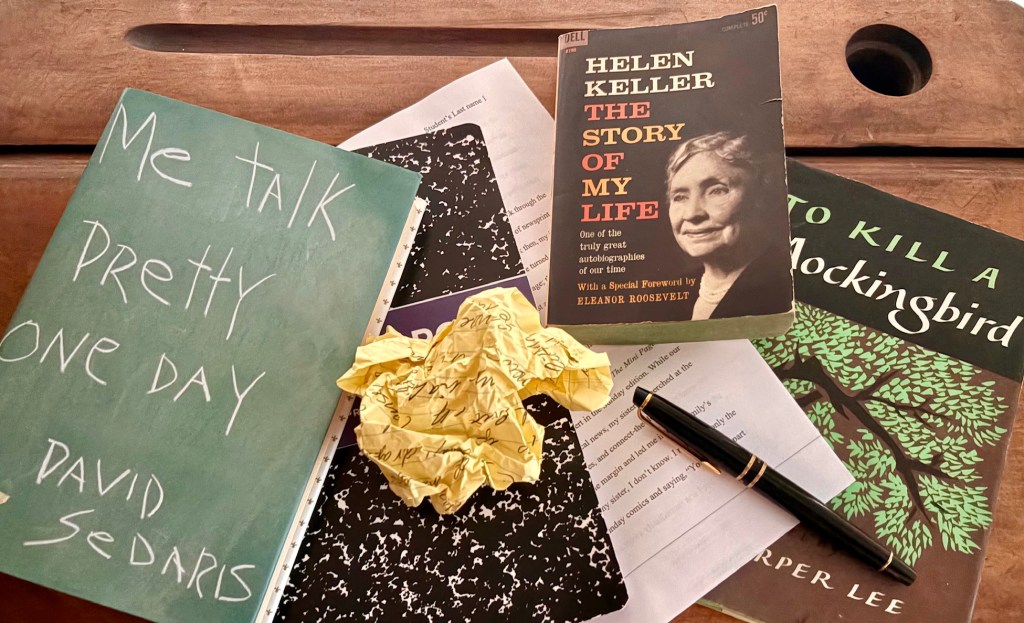

- Did any of the sample essays we examined (“Me Talk Pretty One Day,” “The Day Language Came into My Life,” “A Bridge to Words,” “Creativity is Key,” “Making a Speech: Worst Nightmare to Best Experience”) prove helpful as a model? If so, how?

- What do you consider the strongest element of your literacy narrative?

- What is the title, and at what point in the process did you decide on it? Did you change the title during the writing process? If so, what was the original title?

- What image did you include in your blog that documents part of your writing process away from the screen? Why did you choose that particular image?

- What relevant website did you link to your blog post. Why is that particular site relevant to your narrative?

Journal Exercise

If you reach a stopping point in your reflective writing before the end of the class period, you should begin the journal exercise that I distribuetd in class. Whether you begin the exercise in class today or start it later, you should complete it in your journal before class on Monday, September 15. If you were absent today or misplace your handout, refer to the directions below.

Journal Exercise Directions

- Read “How Long?: Paragraphs, Readers, and Writers” in Writing Analytically (308).

- Compose a one- or two-paragraph journal entry about the excerpt from “The Falling Man,” in which you examine the first paragraph and consider why Tom Junod may have chosen to defy convention and expand his paragraph into one of more than four-hundred words.

- In your journal entry, quote a phrase or sentence from “How Long?: Paragraphs, Readers, and Writers.”

- Introduce your quotation with a signal phrase and follow it with a parenthetical citation. Example: Tom Junod begins “The Falling Man” with a paragraph of more than four-hundred words, even though “[l]ong paragraphs are daunting for both readers and writers” (Rosenwasser and Stephen 308).

- At the end of your journal entry, include the header “Work Cited,” followed by an entry for “How Long?: Paragraphs, Readers, and Writers.” See the sample below.

You are not required to quote “The Falling Man” in your journal entry, but if you do, include a works cited entry for Junod’s article as well. Note that if you quote “The Falling Man” in addition to Writing Analytically, the word “works,” not “work” should appear in your header because you are citing more than one work.

Sample Works Cited Entries

Junod, Tom. “The Falling Man.” Esquire, vol. 140, no. 3, Sept. 2003, pp. 176+. Gale Academic OneFileSelect, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A106423422/EAIM?u=hpu_main&sid=bookmark-EAIM&xid=ce48797f.

Rosenwasser, David and Jill Stephen. “How Long?: Paragraphs, Readers, and Writers.” Writing Analytically, 9th edition. Wadsworth/Cengage, 2024. p. 308.

Note that the entries above are block style for optimum appearance in the WordPress platform. The works cited entries in your handwritten assignments and in the papers you submit to Blackboard ahould have hanging indents. In other words, the first line is flush left and any subsequent lines are indented five spaces or one-half inch.

Next Up

Wordplay Day! To prepare for class, revisit the Dictionary and World Builder pages on the Scrabble website, the Merriam-Webster Scrabble Word Finder page, and review the blog posts devoted to Scrabble.