Biographers don’t usually offer readers more than a glimpse of their subjects’ bookshelves, but Robert Redford’s biographer, Michael Feeney Callan, who is also a novelist and poet, lingers over the books he read—some of which helped shape his vision as an actor and director.

Nothing could calm the restless Redford as a student at Brentwood Elementary until “one teacher’s passionate reading from Farmer Boy and Little House on the Prairie finally got him interested in books” (26). Soon after, his father, Charlie, began the midweek routine of driving Redford and his mother, Martha, to the Santa Monica Public Library. In Redford’s words, “‘I couldn’t wait for Wednesdays, to go through the doors of that library . . . . I’d make straight for Perseus, Zeus, and The Odyssey. Even when I couldn’t read, I’d pick out a word, “Perseus,” and conjure the story from the illustrations”’(qtd. in Callan 26).

When Redford was attending Colorado University, his mother died from complications of septicemia. Less than two years later, his paternal grandmother, Lena, died. For comfort, Redford pored over the novels of Thomas Wolfe, Sinclair Lewis, and Thomas Mann, all of which “struck chords that would surface later in his work” (52), but it was in the pages of Henry Miller’s Nights of Love and Laughter—loaned to him by a classmate who recommended it—where Redford first encountered the frank examination of the world that he had sought in the pages of books. In his words, “‘Yes, he [Miller] talked about hunger and anger and sexual voracity. But it was all in the spirit of saying, “Let’s be honest about human beings.” It was frank, direct human communication, and that was a rare commodity in my life’” (qtd. in Callan 54).

At twenty-two—after dropping out of Colorado University and studying art sporadically in Europe—Redford enrolled at the American Academy of Dramatic Art. There, as an exercise in vocal assessment, an instructor asked the new students to prepare a favorite song to showcase their voices. One of Redford’s classmates, Ginny Burns, recalled that rather than performing the required song, “in a smoldering voice [he] dove into Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘The Raven,’ which he claimed appropriate because it was lyrical. He didn’t merely recite it. He hollered it like an opera, jumping from one window ledge to the next, caroming around the room” (qtd. in Callan 70).

Redford’s passion for Poe’s words didn’t extend to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s—not yet. When he first read The Great Gatsby at Colorado University, he thought it was overrated: “It seemed florid. But when I went back to it, I saw it was something extraordinary, the depiction of human obsessions, and I felt some great screen work could come from it. I found it tantalizing” (qtd. in Callan 250).

The admiration he developed for Fitzgerald’s prose and his close study of it are apparent in his reaction to producer Robert Evans’s initial refusal to consider him for the role of Jay Gatsby because he was a blond. Redford said, “‘I began to think that Evans never read the book. Sure, he liked the idea of doing a Fitzgerald, but he didn’t know the text. Nowhere in it does Fitzgerald say Gatsby’s hair is dark. He says, “His hair was freshly barbered and smoothed back, and his skin was pulled tight over his face.” That’s it. That’s the description”’ (qtd. in Callan 249).

Similarly, Redford’s careful examination of the novel is evident in his observation of a detail that gave him “a hook on which to hang his personal Gatsby” (253). He noticed that “‘Fitzgerald wrote that Jay Gatsby was awkward when he said “old sport”—it didn’t come out of his mouth easily . . . . There’s a whole encyclopedia right there, and it’s from there I started to build up my own version’” (qtd. in Callan 253).

His biographer’s chronicle of Redford’s love of the written word may lead some readers to ask why he didn’t become a writer—but he was one, in fact. Though he never published, he maintained diaries and notebooks throughout his life. And Michael Ritchie, who directed him in Downhill Racer, observed, ‘He was really an author. His writing credit wasn’t on Downhill or Jeremiah Johnson but he was really an author as much as David Rayfiel, or even [James] Salter’” (qtd. in Callan 220). Rayfiel himself agreed, noting, “‘He had a writer’s eye and ear more than any actor I ever worked with’” (qtd. in Callan 271).

When Hume Cronyn asked Redford how he wanted Sundance to be remembered in one hundred years, Redford replied, “‘Like Walden Pond’” (qtd. in Callan 374). It’s a testament to Redford’s life as a reader that his answer didn’t refer to the film character for whom his writers’ colony and non-profit are named, but instead to the wooded haven he discovered in the pages of Henry David Thoreau.

Work Cited

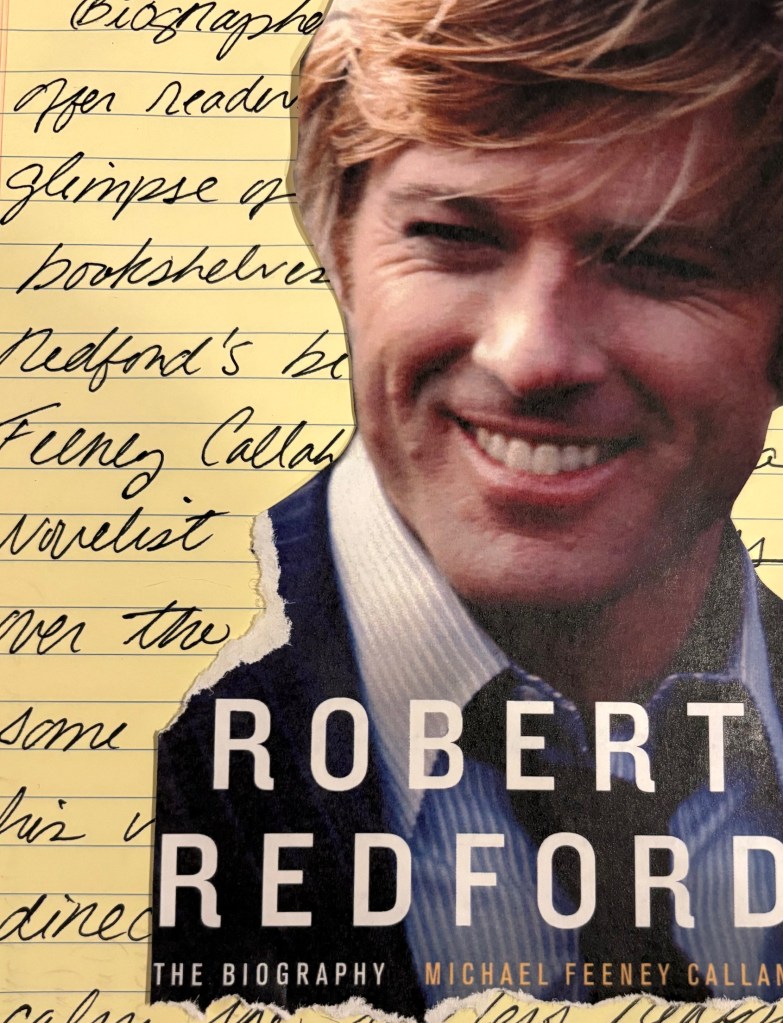

Callan, Michael. Feeney. Robert Redford: The Biography. 2011. Vintage, 2012.