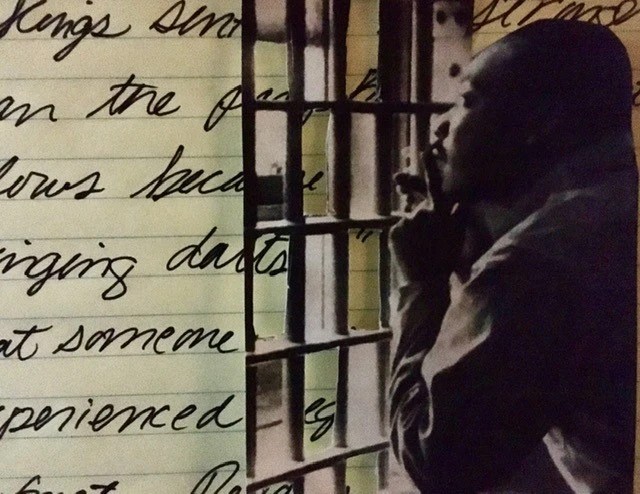

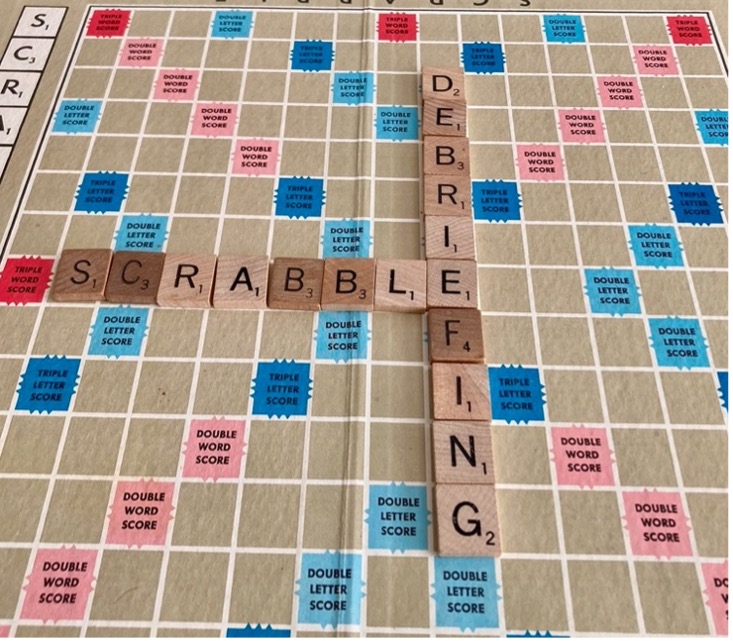

Yesterday before you you began your revision work, we examined a page (pictured above) from Harper Lee’s novel To Kill a Mockingbird. That page from the first chapter serves as a valuable model for three narrative elements: summary, scene, and dialogue–at least two of which will figure in your literacy narrative.

The first paragraph of the passage summarizes the characters’ circumstances, designating the “summertime boundaries” (12) within which the narrator, Jean Louise, “Scout,” Finch, and her older brother, Jem, may play outdoors. The short one-sentence paragraph that follows continues the summary, informing readers that the summer Scout has just summarized is the one in which Dill (Charles Baker Harris) first visits Maycomb, Alabama.

With the first words of the next paragraph, “[e]arly one morning,” Scout shifts from summary to scene (12). All of the remaining paragraphs except the final one continue the scene with dialogue. Scout returns to summary with the words “Dill was from Meridian” (12).

Note that Harper Lee begins a new paragraph whenever the speaker changes. Also note that every line of dialogue does not include a dialogue tag, such as “he said” or “she said.” If a passage of dialogue includes only two speakers, none of the paragraphs require dialogue tags after the speakers’ first lines because the start of a new paragraph signals to the reader that the other person is speaking. If a dialogue includes three or more speakers–such as Scout’s conversation with Jem and Dill–occasional tags are essential.

Lessons in Punctuation

The excerpt from To Kill a Mockingbird also demonstrates how to use a variety of punctuation marks, including em dashes, hyphens, and commas.

- Harper Lee uses em dashes to set off “Miss Rachel’s rat terrier was expecting” (12) from the rest of the sentence because it is nonessential. It adds details, but the sentence can function without them. An em dash is used before and after phrases that are nonessential. Note that there is no space before or after the dash, which is made with two strikes of the hyphen key.

- Jem asks if Dill is “four-and-a-half”? Hyphens appear between those words because multiple-word numbers are hyphenated.

- Near the end of the excerpt, “Mississippi” and “Miss Rachel” (12) are both set off by commas because those details are nonessential. Commas are used to set off single words and short phrases of nonessentials the way that em dashes are used to set off longer units of words.

Work Cited

Lee, Harper. To Kill a Mockingbird. Lippincott, 1960. p. 12.

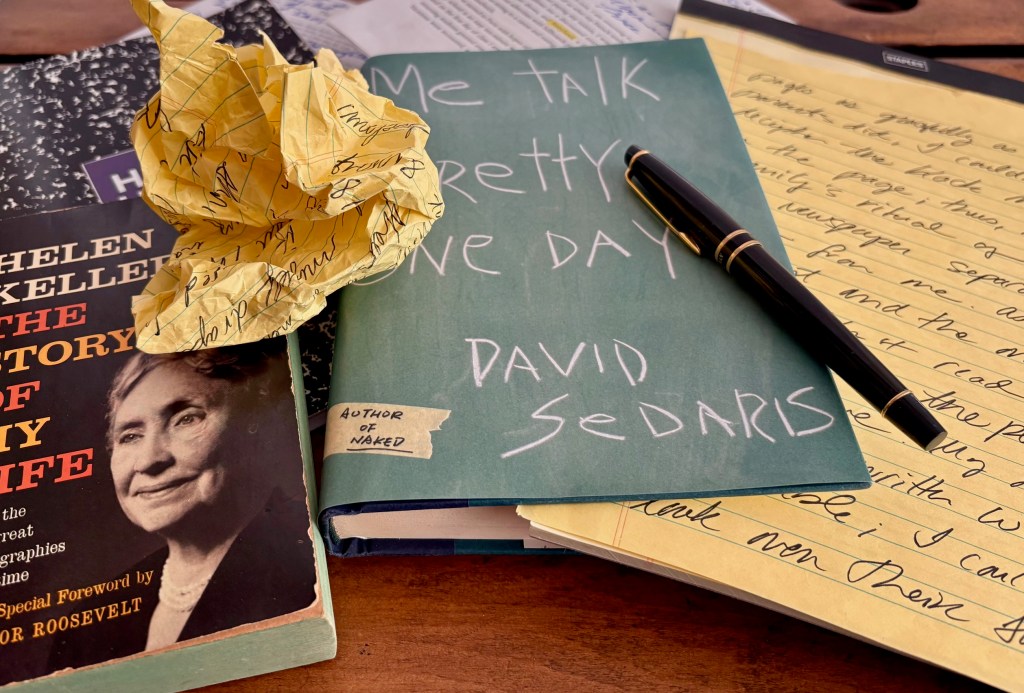

Congratulations to Davis Smith for winning a copy of Helen Keller’s autobiography, The Story of My Life, in yesterday’s raffle.

Next Up

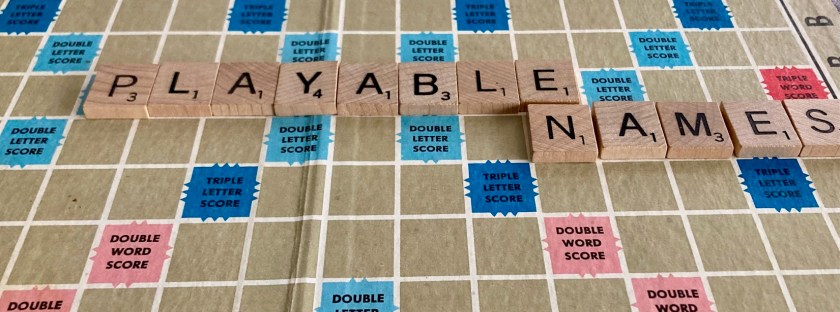

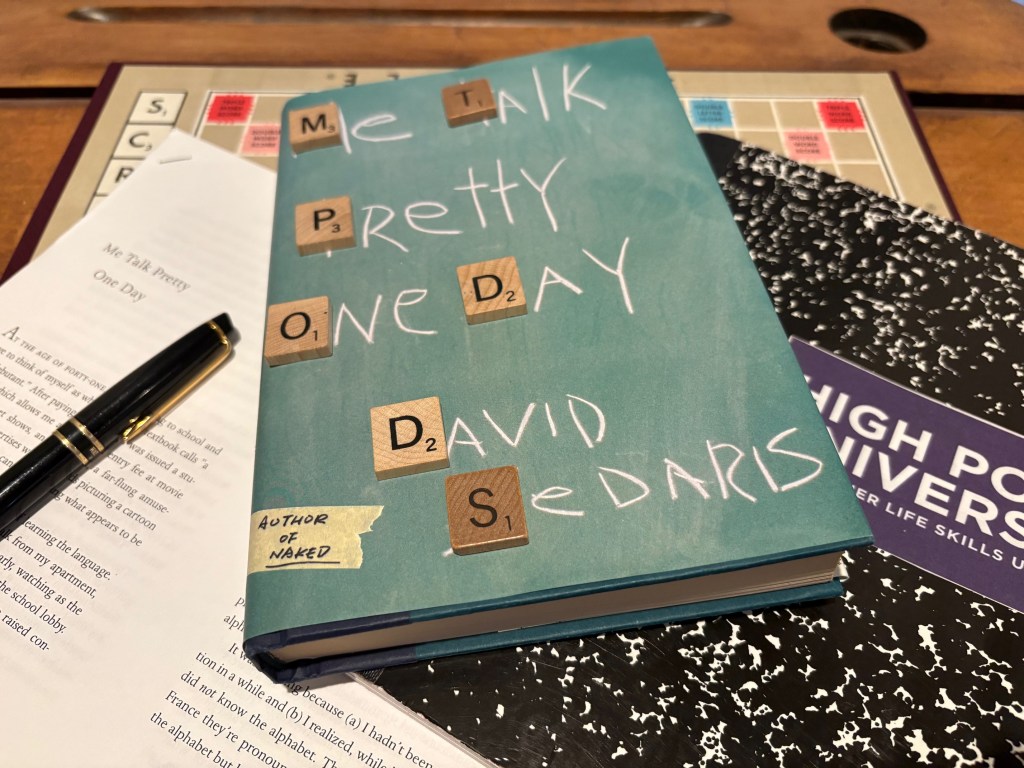

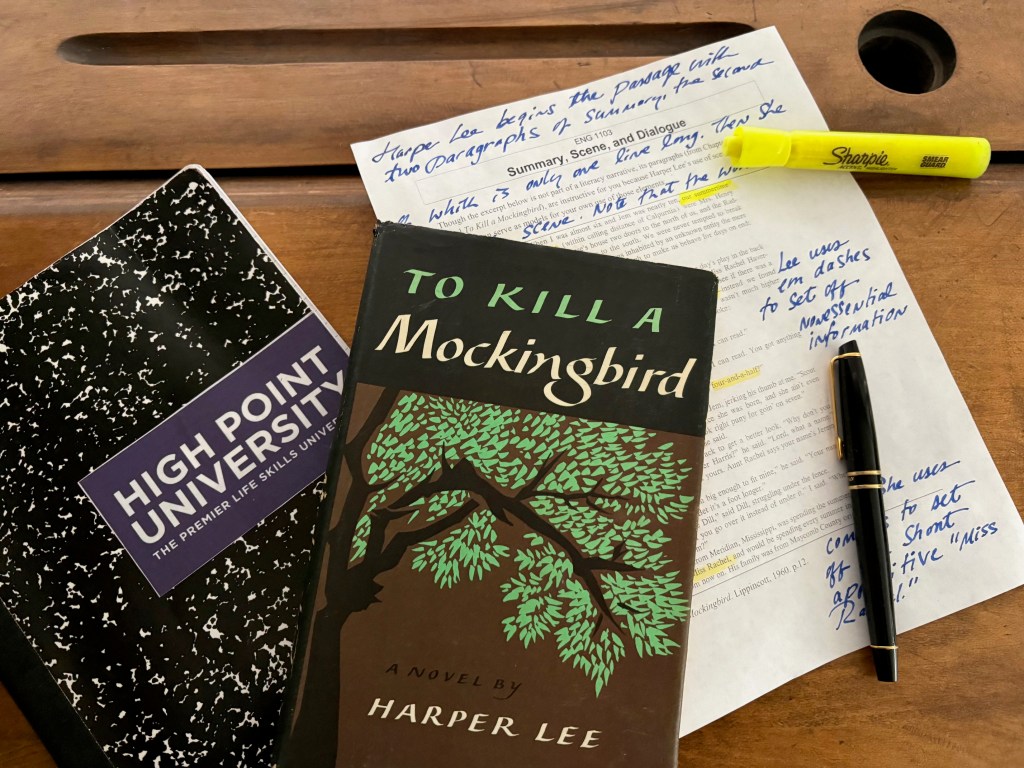

Wordplay Day! To prepare for class, revisit the Dictionary and World Builder pages on the Scrabble website, or the Merriam-Webster Scrabble Word Finder page, and review the blog posts devoted to Scrabble.