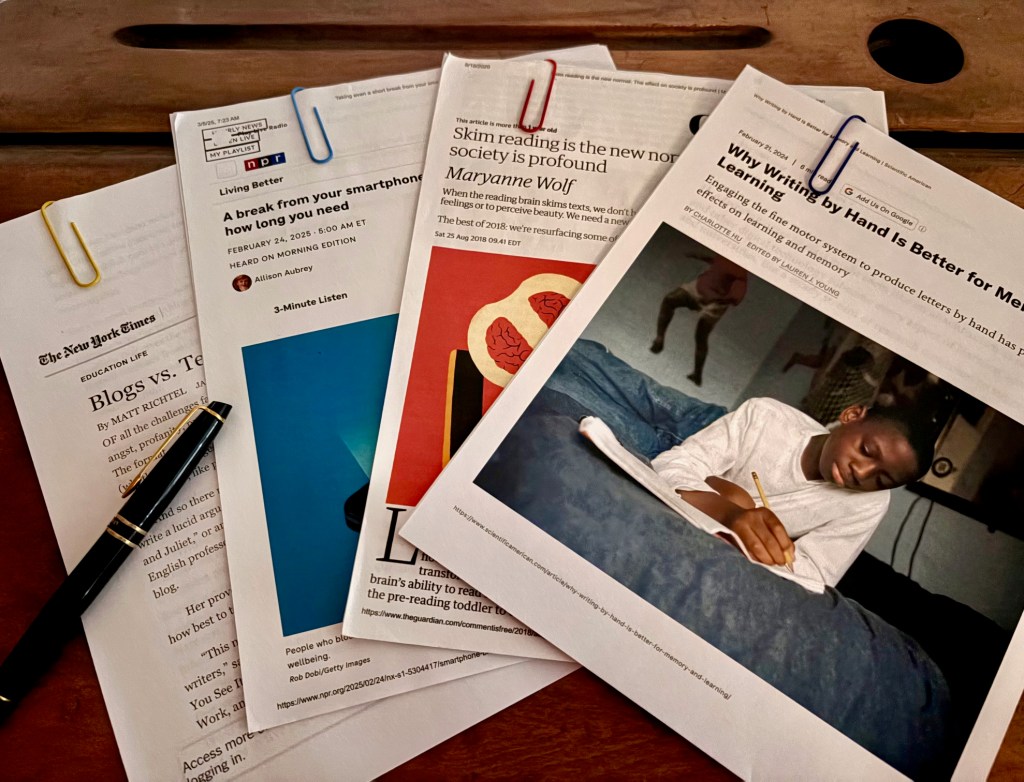

The four articles that served as the subjects for your group presentations are all secondary sources: texts that address information originally presented in primary sources. Primary sources include research studies and other original works, such as historical documents, essays, and fiction. Each of the essays, the short story, the letter, and the chapter that you read previously for class can serve as primary sources for your research. For example, David Sedaris‘s “Me Talk Pretty One Day” is a primary source for a study of Sedaris’s writing.

- In “Blogs vs. Term Papers,” Matt Richtel reports on the findings of the National Survey of Student Engagement and a study of high school writing requirements conducted by William H. Fitzhugh, editor of The Concord Review, as well as the writing curricula of then-Duke University Professor Cathy Davidson and Stanford Professor Emerita Andrea Lunsford.

- In “Writing by Hand is Better for Memory and Learning,” Charlotte Hu reports on research published in Frontiers in Psychology, conducted by Audrey van der Meer and Ruud van der Weel at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

- In “A Break from Your Smartphone,” Allison Aubrey reports on research conducted by Noah Castelo, Kostadin Kushlev, Adrian F. Ward, Michael Esterman, and Peter B. Reiner, which was published in PNAS NEXUS, the journal of the National Academy of Science.

Although Maryanne Wolf’s “Skim Reading is the New Normal” cites research originally published in primary sources, she is not reporting on that research objectively. Instead, she argues that in light of researchers’ findings, “[w]e need to cultivate a new kind of brain: a ‘bi-literate’ reading brain capable of thought in either digital or traditional mediums” (par. 12). If you look at the heading on your copy of Wolf’s article, you will see the word opinion, which indicates that her article appeared in the opinion section of The Guardian‘s website and on the Op-Ed page of the physical paper.

Informed opinion pieces–such as Wolf’s, which draws on scholarly research–are suitable sources for your research, but it’s important to recognize the difference between reporting and commentary.

Great Britain’s The Guardian, which published Wolf’s article, and The New York Times, which published Richtel’s “Blogs vs. Term Papers,” are two of the most well-regarded newspapers of record, known for their accuracy and high-quality reporting. NPR (National Public Radio), which aired Aubrey’s “A Break from Your Smartphone,” is another premier news outlet. The magazine Scientific American, which published Hu’s “Writing by Hand is Better for Memory and Learning,” is yet another first-rate publication, one known for its authoritative and accessible coverage of science and technology news, written for a general audience.

AP Style vs. MLA Style

As you read the four articles that served as your presentation subjects, you probably noticed some differences among their styles and MLA (Modern Language Association) style, which you use for paper assignments in English 1103 and other courses in the humanities. Most news publications use AP (Associated Press) or their own in-house style book that shares many of AP’s rules. One of reason style rules are difficult to remember is the differences among the requirements. Here are some of the important distinctions between AP style and MLA:

- In AP style, a sentence may begin with a quotation. In MLA style, a quotation must be introduced with a signal phrase. Otherwise, it is considered a dropped quotation.

- AP style does not include parenthetical citations. In MLA style, quotations and paraphrases are followed by parenthetical citations–unless the sources are interviews or other nonprint sources.

- In AP style, titles of publications are not enclosed in quotation marks or italicized. In MLA style, titles of short works are enclosed in quotation marks; titles of longer works are italicized (underlined in longhand).

- Almost all numbers are expressed as figures in AP style. In MLA style, any number that can be expressed in one or two words is written as a word.

- AP style omits the Oxford or serial comma, the comma before and in a series of three or more. Most publications other than newspapers use the Oxford or serial comma, and MLA advocates its use.

- In AP style, an em dash is preceded and followed by a space. MLA style requires no space before or after an em dash.

Next Up

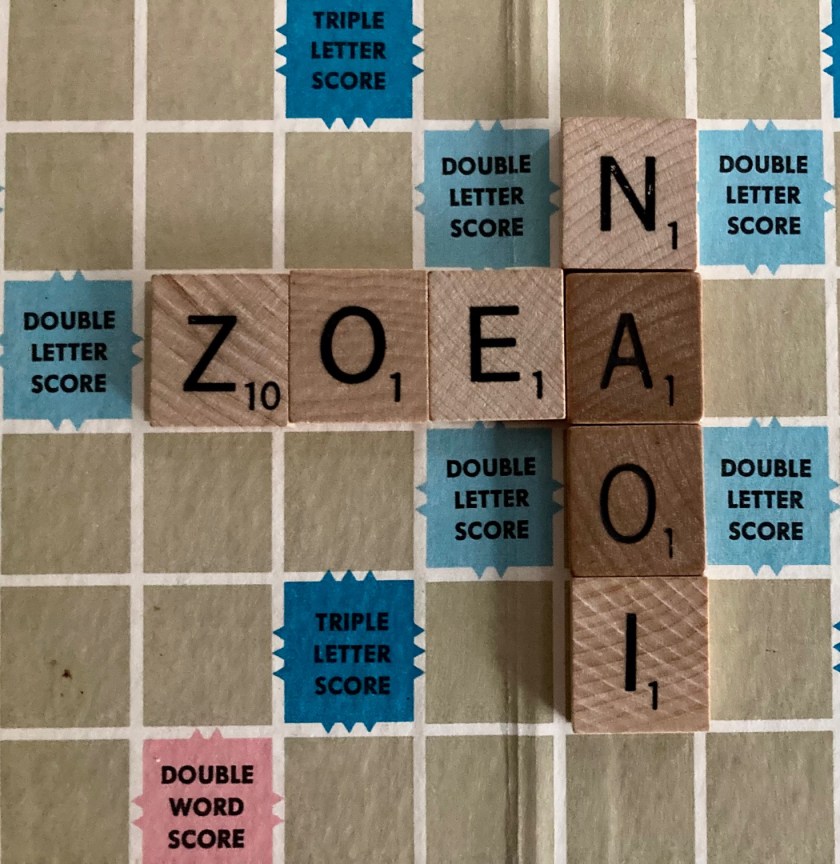

Wordplay Day! To prepare for class, revisit the Dictionary and World Builder pages on the Scrabble website, or the Merriam-Webster Scrabble Word Finder page, and review the blog posts devoted to Scrabble tips, including this one.