Narrative Conflict or Tension

Last week I advised you to Study Spiegelman’s scenes closely. As you continue to read Maus, and as you prepare to write your first essay for English 111, your literacy narrative, note which panels of Spiegelman’s convey conflict, either a character’s inner conflict or a character’s conflict with another character. Conflict, which is essential to narrative, appears on virtually every page of Maus.

The first half of Chapter 2, “The Honeymoon,” depicts six conflicts or problems:

- Vladek combatting his medical condition (heart disease, diabetes)

- the policemen’s pursuit of Anja

- the interrogation of Anja’s aide, the seamstress, Miss Stefanska

- Art questioning his father’s storytelling

- Anja’s struggles with post-partum depression, and

- the train passengers facing the threat of the Nazi regime, signified by the flag in the center of the page (32).

Scene and Summary

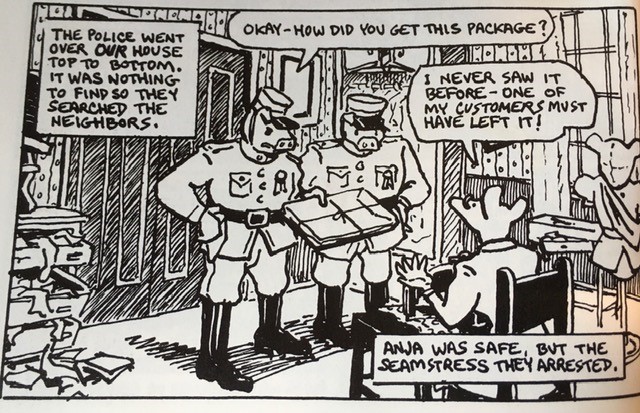

As a comic, Maus consists primarily of scenes but it includes summary as well. In the panel below, which depicts Miss Stefanska’s interrogation by the Polish police, the scene is depicted with the panel’s drawing and its speech balloons. Spiegelman presents summary in the rectangles.

Scene and summary are the building blocks of narratives. Simply put, scenes show and summaries tell. Narratives can consist primarily of scenes, but ones that rely heavily on summary don’t capture our imagination. As you plan your literacy narrative, keep this in mind: Readers would rather be shown than told.

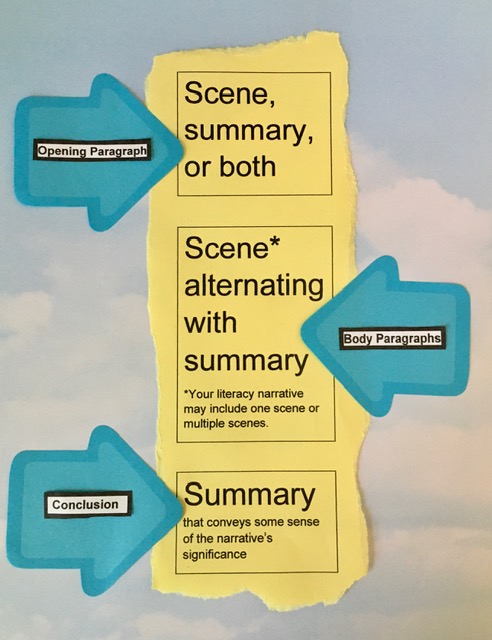

The paper-craft graphic below illustrates the organization of scene and summary in a narrative essay.

Dialogue

Maus demonstrates the important role that dialogue often plays in narrative, but it doesn’t show how dialogue is presented in an essay. In comics, dialogue appears in speech balloons. Prose narratives (essays, short stories, novels, and book-length nonfiction) present dialogue with lines of speech enclosed in quotation marks and with dialogue tags. A dialogue tag is a short phrase at the beginning, in the middle, or at the end of the dialogue that attributes the dialogue to a particular person or character.

“Have you chosen a topic for your literacy narrative?” she asked.

In the sentence above, she asked is the dialogue tag.

When you write dialogue, you begin a new paragraph whenever the speaker changes. That’s why paragraphs of dialogue are generally short, often only one line.

Consider the dialogue below, from Annie Dillard’s memoir, An American Childhood:

In the first paragraph, Annie Dillard summarizes how her mother would tell her to spell words. In the second paragraph, Dillard moves to the scene of one particular evening, the night when her mother says there’s a deer in the hall. Only the first of the three short paragraphs that follow the summary includes a dialogue tag. The other two don’t need tags because the new paragraph itself, the indentation of five spaces, signals a change in the speaker.

Once you’ve established who the speakers are in a dialogue between two people, you don’t need to include dialogue tags.

Notice that the first and last paragraphs include single quotation marks within the lines of dialogue. In the first paragraph, the words poinsettia and sherbet are enclosed in single quotation marks because words referred to as words are enclosed in quotation marks. Since the two words are contained within a longer quotation, Dillard’s mother’s line of dialogue, the words are enclosed in single quotation marks.

In the last paragraph, the words I know are enclosed in single quotation marks because the mother is quoting her daughter.

Words referred to as words in dialogue and quotations within lines of dialogue are enclosed in single quotation marks.

For more information on quotation marks, see A Writer’s Reference (279-80).

Look to the passage that follows as another model for your literacy narrative. Here, Annie Dillard recounts seeing an amoeba for the first time:

Finally late that spring I saw an amoeba. The week before, I had gathered puddle water from Frick Park; it had been festering in a jar in the basement. This June night after dinner I figured I had waited long enough. In the basement at my microscope table I spread a scummy drop of Frick Park puddle water on a slide, peeked in, and lo, there was the famous amoeba. He was as blobby and grainy as his picture; I would have known him anywhere.

Before I had watched him at all, I ran upstairs. My parents were still at table, drinking coffee. They, too, could see the famous amoeba. I told them, bursting, that he was all set up, that they should hurry before his water dried. It was the chance of a lifetime.

Father had stretched out his long legs and was tilting back in his chair. Mother sat with her knees crossed, in blue slacks, smoking a Chesterfield. The dessert dishes were still on the table. My sisters were nowhere in evidence. It was a warm evening; the big dining-room windows gave onto blooming rhododendrons.

Mother regarded me warmly. She gave me to understand that she was glad I had found what I had been looking for, but that she and Father were happy to sit with their coffee, and would not be coming down. She did not say, but I understood at once, that they had their pursuits (coffee?) and I had mine. She did not say, but I began to understand then, that you do what you do out of your private passion for the thing itself.

I had essentially been handed my own life, in subsequent years my parents would praise my drawings and poems, and supply me with books, art supplies, and sports equipment, and listen to my troubles and enthusiasm, and supervise my hours, and discuss and inform, but they would not get involved with my detective work, nor hear about my reading, nor inquire about my homework or term papers or exams, nor visit the salamanders I caught, nor listen to me play piano, nor attend my field hockey games, nor fuss over my insect collection. My days and nights were my own to plan and fill.

Those paragraphs from An American Childhood don’t include any direct quotations. In the second paragraph, Dillard recounts what her mother said, but she doesn’t present it as dialogue. If the exact words spoken aren’t crucial to a scene, you can present the conversation indirectly, as Dillard does above.

Narratives Don’t Have to Center on Dramatic Events

The excerpts that you’ve just read from An American Childhood demonstrate how to write dialogue and shift between scene and summary. And perhaps most importantly, they demonstrate this: Narratives don’t have to center on dramatic events.

If you think that you don’t have a story to write as your literacy narrative, look again at Dillard’s depiction of herself as a student of the natural world. There’s no dramatic conflict, but there’s desire. First, she wants to see an amoeba, something she’s never seen before. Second, she wants her parents to share her excitement, but they don’t. With her microscope, Annie Dillard develops her knowledge of nature, but the larger learning experience that takes place is her realization that “you do what you do out of your private passion for the thing itself” (149). She has “essentially been handed [her] own life” (149).

What quiet, significant learning experience of yours has lingered in your mind? Your answer to that question could be the start of your literacy narrative.

Literacy Narrative Topics

I included your options in the previous blog post and am listing them here as well:

- any early memory about writing, reading, speaking, or another form of literacy that you recall vividly

- someone who taught you to read or write

- someone who helped you understand how to do something

- a book that has been significant to you in some way

- an event at school that was related to your literacy and that you found interesting, humorous, or embarrassing

- a literacy task that you found (or still find) especially difficult or challenging

- a memento that represents an important moment in your literacy development

- the origins of your current attitudes about writing, reading, or speaking

- creating and maintaining your WordPress blog

Length Requirement

Your literacy narrative should be no fewer than five-hundred words. I encourage you to challenge yourself to exceed the minimum.

When to Begin

You are not required to begin your literacy narrative before the class period devoted to drafting, but you are welcome to sketch out ideas and begin drafting in your journal.

Dillard, Annie. An American Childhood. Harper & Row, 1987.

Spiegelman, Art. Maus I. Pantheon, 1986.