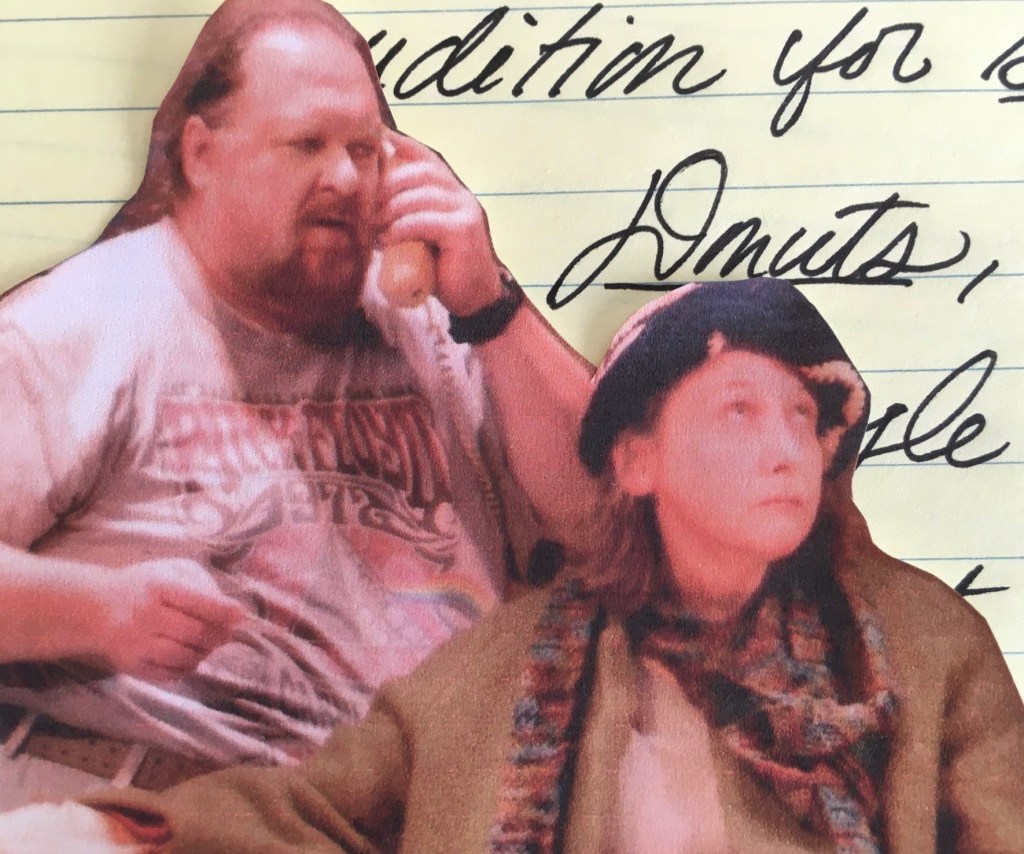

When I decided to audition for Superior Donuts, Lady Boyle was not on my radar. What had drawn me to the play was its writer, Tracy Letts. A few years earlier, I had seen a production of Letts’ Pulitzer Prize-winning tragicomedy August, Osage County and had left the theatre hoping that I would someday have the chance to perform a role he had written.

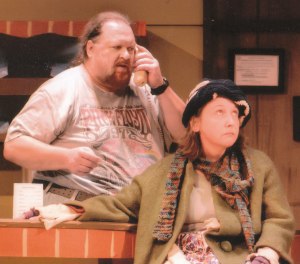

Then came Superior Donuts. As soon as I read the character list in the audition notice, I knew I wanted to read for the role of Randy Osteen, a woman Letts described as a forty-nine-year-old Irish American cop. (As a fair-skinned forty-eight-year-old, I seemed like a good fit.) After I auditioned for Randy, the director asked me to read for the other female role, Lady Boyle. I didn’t give her much thought until the cast announcement arrived in my inbox. When I read the director’s email, I was elated to discover that I had been cast but surprised that I wasn’t Randy. Instead, I was Lady Boyle, the seventy-two-year-old bag lady.

The role of Lady Boyle was appealing but daunting. An alcoholic living in her own alternate reality, she was a woman whose foul-mouthed nonsense unexpectedly gave way to moments of clarity and wisdom. Often when I think of her, I am reminded of Letts’ decision to name her Boyle even though her name is never spoken in the play; the other characters simply call her “Lady.” For Letts, the name Boyle granted Lady her humanity, which is what I aimed for as I worked to become her. As I learned her lines and developed the mannerisms that would accompany them, I hoped the audience would see her as more than a type.

That’s how the other characters saw her, with the exception of the donut shop’s owner, Arthur Przybyszewski. In the second act, when Arthur asks about her children, he inquires not as a shop owner making small talk but as a parent struggling to reconcile with his daughter. As Lady Boyle and Arthur sit together at a table in his shop, she tells him that she has outlived three of her four children, and recounts their deaths:

LADY: One of ‘em got shot by the coppers in a gasoline station stick-up. One of ‘em had a grabber, mowin’ the yard. And one of them died in the crib with that disease. Where the spinal cord gets a mind of its own and decides it don’t want to live trapped inside those little bones no more. You know what I’m talkin’ about?

ARTHUR: I don’t think so.

LADY: Your spinal cord gets it in its head to go free and slitherin’ out into the world. That’s what killed my little Venus. Her spinal cord got its own notions. (44)

Delivering those lines of Lady Boyle’s—and finding myself speaking some of them through tears—sustained me during a difficult time. (As Lady Boyle would say, it “happens to all of us.”) My husband had been laid off from his job in Richmond two years earlier. We had landed on our feet in North Carolina, where he was working again as an editor, but I was an invisible adjunct longing for the full-time teaching job and the community of colleagues I had left behind.

Becoming Lady Boyle made me feel whole again.

Letts, Tracy. Superior Donuts. Dramatists Play Service, 2010.

It started with the rock. Actually, it started for me with the rock. For you, the story would start elsewhere, I’m sure. I came across the rock, now your rock, in the backyard shortly after my husband and I moved into the house. I was struck by the granite’s natural beauty, its graceful belt of pale stripes. I moved the rock from its cradle of broken bricks and overgrown grass to a spot on the corner of the deck. There I could see it from the window in the kitchen door, and from there I would soon see you, too.

It started with the rock. Actually, it started for me with the rock. For you, the story would start elsewhere, I’m sure. I came across the rock, now your rock, in the backyard shortly after my husband and I moved into the house. I was struck by the granite’s natural beauty, its graceful belt of pale stripes. I moved the rock from its cradle of broken bricks and overgrown grass to a spot on the corner of the deck. There I could see it from the window in the kitchen door, and from there I would soon see you, too. Now, as I continue to forage for the right words, I pause in my writing and picture you back on your perch, contemplating life. The stripes in the granite reflect the ones that border your curved back.

Now, as I continue to forage for the right words, I pause in my writing and picture you back on your perch, contemplating life. The stripes in the granite reflect the ones that border your curved back. A flannel shoe bag, a pile of mini craft sticks, and a repurposed Q-Tip travel box: These items are in my hands most days. They’re often in the hands of my students as well. Any of them who walk into the classroom early—before the beginning of the hour—and spot the bag and the box of sticks on the front desk know that they’ll be working in groups that day, at least for part of the class period. Their job, if they choose to volunteer, is to make random groups by drawing sticks, which are labeled with the students’ names.

A flannel shoe bag, a pile of mini craft sticks, and a repurposed Q-Tip travel box: These items are in my hands most days. They’re often in the hands of my students as well. Any of them who walk into the classroom early—before the beginning of the hour—and spot the bag and the box of sticks on the front desk know that they’ll be working in groups that day, at least for part of the class period. Their job, if they choose to volunteer, is to make random groups by drawing sticks, which are labeled with the students’ names. To me, all of these noises are sounds of collaboration and community building, of students not sitting passively but instead taking an active role in preparing for class. A flannel shoe bag, a pile of mini craft sticks, and a repurposed Q-Tip travel box: In the classroom these are small, good things.

To me, all of these noises are sounds of collaboration and community building, of students not sitting passively but instead taking an active role in preparing for class. A flannel shoe bag, a pile of mini craft sticks, and a repurposed Q-Tip travel box: In the classroom these are small, good things.

I bought my first pair of Chuck Taylors at the Salvation Army when I was in high school. My then-boyfriend had introduced me to thrift-store shopping, much to my parents chagrin. They didn’t mind when my boyfriend and I combed the local flea market and thrift stores for vinyl records, but buying clothes there was a different matter.

I bought my first pair of Chuck Taylors at the Salvation Army when I was in high school. My then-boyfriend had introduced me to thrift-store shopping, much to my parents chagrin. They didn’t mind when my boyfriend and I combed the local flea market and thrift stores for vinyl records, but buying clothes there was a different matter.

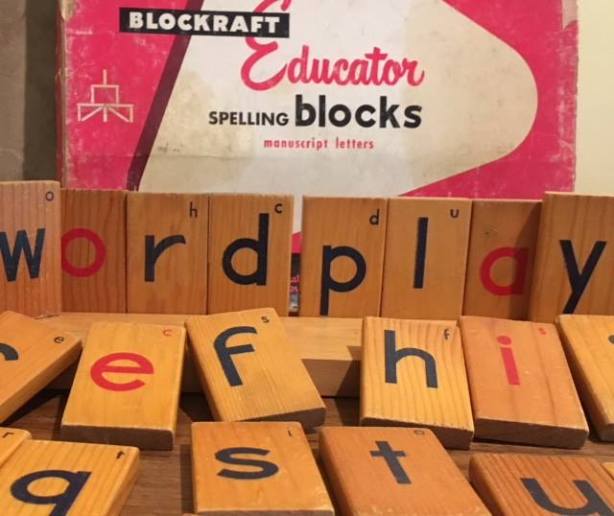

I never became an auction-goer, but I share my parents’ fascination with objects from the past. And I can trace the allure of artifacts back to those outings with them. Rather than standing and listening to an auction chant, I prefer the quiet pastime of browsing the shelves of antique shops and thrift stores. What appeals to me about such excursions is the possibility of the unexpected find: most recently a set of wooden letter blocks at

I never became an auction-goer, but I share my parents’ fascination with objects from the past. And I can trace the allure of artifacts back to those outings with them. Rather than standing and listening to an auction chant, I prefer the quiet pastime of browsing the shelves of antique shops and thrift stores. What appeals to me about such excursions is the possibility of the unexpected find: most recently a set of wooden letter blocks at