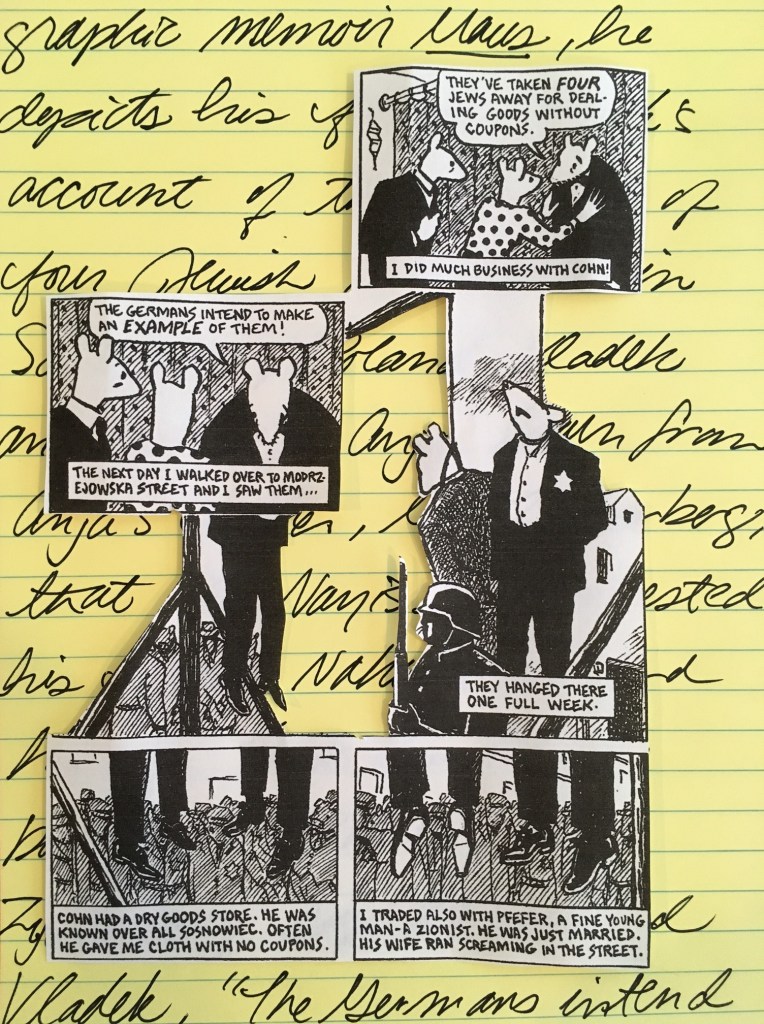

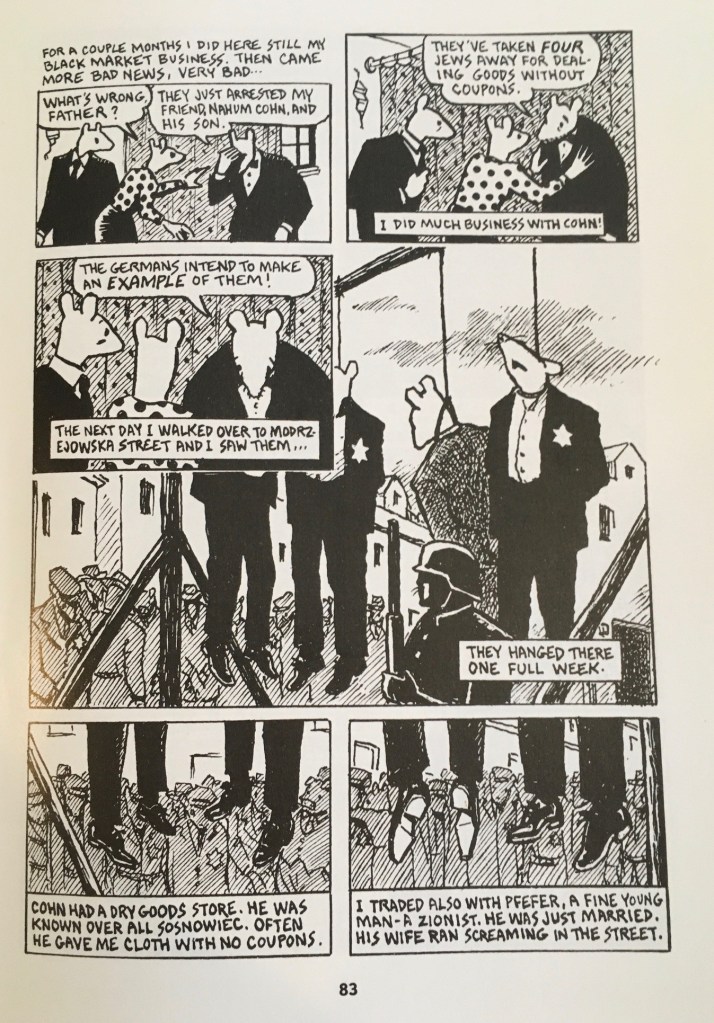

In Chapter 4 of Art Spiegelman’s graphic memoir Maus, he depicts his father Vladek’s account of the hangings of four Jewish merchants in Sosnowiec, Poland. Vladek and his wife, Anja, learn from Anja’s father, Mr. Zylberberg, that the Nazis have arrested his friend Nahum Cohn and his son. With his head bowed in sorrow, Mr. Zylberberg says to Anja and Vladek, “The Germans intend to make an example of them!” (83). That image of Mr. Zylberberg speaking with Vladek and Anja overlays the larger panel that dominates the page, one that depicts the horror that Mr. Zylberberg anticipates: the murder of his friend Nahum Cohn, Cohn’s son, and two other Jewish merchants. That haunting panel and the smaller ones that frame it illustrate the complexity of Spiegelman’s seemingly simple composition. His rendering of the panels of the living in conjunction with the fragmented panels of the hanged merchants simultaneously conveys connection and separation: both the grieving survivors’ ties to the dead and the hanged men’s objectification at the hands of the Nazis.

The placement of the overlaying panel not only hides part of the horror behind it, but it also connects Vladek’s father-in-law to one of the victims. Mr. Zylberberg’s head and torso appear directly above the suspended legs and feet of one of the hanged men, creating an image that merges the two.

Spiegelman further emphasizes the mourners’ identification with the hanged men by extending two of the nooses’ ropes upward to the smaller panel above them, linking the living to the dead. Additionally, Spiegelman underscores the link with Vladek’s line of narration at the bottom of the smaller panel: “I did much business with Cohn!” (83). The word “with” appears directly above the rope, punctuating the connection between both Nahum Cohn and his friend Mr. Zylberberg and Zylberberg’s son-in-law, Vladek.

While the panels of the hangings yoke the living to the dead, Spiegelman’s presentation of the hanged men in fragments also objectifies them. The final panels on the page depict only their shoes and part of their pant legs suspended above the onlookers, images that may evoke in some readers thoughts of the last remnants of the Jews who stepped barefoot into the gas chambers of Auschwitz.

Whether the hanged men’s shoes call to mind those mountains of leather left behind by the Jews, the separation of their lower legs and feet from the rest of their bodies turns them into something less than human—not people, but mere parts. Thus, Spiegelman creates a picture of the hangings that illustrates both the mourners’ identification with the victims and the Nazis’ perception of the Jews as less than human: the malignant ideology that the artist has pinpointed “at the very heart of the killing project.”

Spiegelman’s transformation of the Nazi propaganda portrayals of Jews as rats remains an astounding achievement thirty-five years after the publication of the first volume of Maus. But seeing the hanged merchants in Modrzejowska Street in the midst of the George Floyd murder trial in Minneapolis and less than three months after the January 6 Capitol riot reminds readers that the panels of Spiegelman’s memoir have grown more prescient. The nooses evoke images of Officer Derek Chauvin’s knee on George Floyd’s neck, the January 6 chants to hang the Vice President, and a T-shirt glimpsed in the Capitol crowd, one with a Nazi eagle below the acronym “6MWE” (Six Million Wasn’t Enough), a reference to the numbers of Jews slaughtered in the Holocaust. Our heads are bowed in sorrow with Mr. Zylberberg’s. The strange fruit of our past, both distant and recent, should seem far stranger.

Works Cited

Spiegelman, Art. Maus I. Pantheon, 1986.

—. “Why Mice?” Interview by Hillary Chute. The New York Review of Books, 20 Oct. 2011, https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2011/10/20/why-mice/.