Today as you continue to plan and draft, look to the essay excerpts I’ve included here for ideas and inspiration as well models for developing your own narrative through description, narration, classification, and definition.

Developing with Description

First, consider the paragraph that follows from a literacy narrative written by a student at the University of Texas at El Paso. In the first paragraph of her essay, the writer, Ana-Jamileh Kassfy, introduces readers to her family’s auto repair shop. In the second paragraph (the one below), she describes her role in the auto shop with details that lead to the incident at the center of the narrative.

From “Automotive Literacy”

Since I come from a family whose life revolves around cars, and since I practically lived at the auto shop until I was able to drive, you’d think that I’d understand most of the jargon a mechanic would use, right? Wrong. During my first sixteen years of life, I did manage to learn the difference between a flathead and a Torx screwdriver. I also learned what brake pads do and that a car uses many different colorful fuses. However, rather than paying attention to what was happening and what was being said around me, most of the time I chose to focus on the social aspect of the business. While everyone was running around ordering different pads, filters, and starters or explaining in precise detail why a customer needed a new engine, I chose to sit and speak with customers and learn their life stories. Being social worked for me–until it didn’t. (85)

The writer, Kassfy, develops the second paragraph using description as her pattern of organization, specifically by describing what she has and hasn’t learned about her family’s auto shop. What she hasn’t learned (because she focused on the social aspect of the business) leads to the incident at the center of the narrative, which she introduces with the line “until it didn’t.”

For more on developing paragraphs with description, see A Writer’s Reference (45-46).

Developing with Narration and Classification

In “Wet Dogs & White People,” Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Harvard Professor and host of PBS’s Finding Your Roots, begins with a one-sentence paragraph hook followed by a memory within a memory: a car ride with his daughter in which he recounts learning to read and write.

From “Wet Dogs & White People”

You just wouldn’t know it from Mama.

I remember the first time I got angry with my older daughter, Maggie. Not the angry that a parent gets when he’s tired, or irritable, or stressed. But angry, deep-down angry, angry like: Do I know this person I’ve helped bring into the world and have been living with for seven or eight years? We were driving along the highway that connects Piedmont to Cumberland, and I was going on about Mama, about how she had taught me to read and write in one day in the kitchen of our second house, down Rat Tail Road. (“You want to learn how to write?” was all she had asked me. And I had said yes, so she wrote out all of the letters in printing and in script, and we made them together on our red kitchen table.) (84)

After opening his essay with a one-sentence paragraph hook, Gates begins his narration with a memory, then interrupts it with classification. Note how Gates begins to develop his paragraph by classifying types of anger before he returns to the narration that leads to the memory within a memory.

For more on developing paragraphs with narration and classification, see A Writer’s Reference (45, 48).

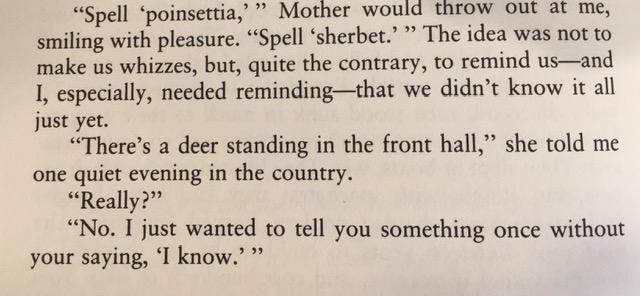

Developing with Definition

Novelist Amy Tan, author of The Joy Luck Club, begins her essay “Mother Tongue” with a definition—first by defining herself by what she isn’t, then by turning to how she defines herself as a writer.

From “Mother Tongue”

I am not a scholar of English or literature. I cannot give you much more than personal opinions on the English language and its variations in this country or others.

I am a writer. And by that definition, I am someone who has always loved language. I am fascinated by language in daily life. I spend a great deal of my time thinking about the power of language—the way it can evoke an emotion, a visual image, a complex idea, or a simple truth. Language is the tool of my trade. And I use them all—all the Englishes I grew up with. (462)

In the first paragraph of her essay, Tan defines herself by what she is not (“a scholar of English or literature”). She develops the second paragraph by expanding her definition of what it means to her to be a writer, a definition that serves as a lead-in to her exploration of her identity as someone who grew up hearing and speaking more than one form of English: her own standard English and the nonstandard English of her immigrant mother.

For more on developing paragraphs through definition, see A Writer’s Reference (48-49).

Works Cited

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. “Wet Dogs & White People.” Colored People. Knopf, 1994, pp. 29-39.

Hacker, Diana, and Nancy Sommers. A Writer’s Reference. GTCC Custom 9th ed., Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2018.

Kassfy, Ana-Jamileh. “Automotive Literacy.” The Norton Field Guide to Writing with Readings and Handbook. 5th ed., by Richard Bullock, Maureen Daly Goggin, and Francine Weinberg, 2019, pp. 84-86.

Tan, Amy. “Mother Tongue.” The Norton Book of Personal Essays. Edited and with an Introduction by Joseph Epstein. W.W. Norton, 1997. pp. 462-68.

You’ve Got to . . .

For the third installment in our You’ve-Got-To series, I offer an assignment that focuses on “Keep the Wolves Away” by Uncle Lucius. In it, the writer addresses the song’s themes of overcoming adversity and the dynamics of parent-child relationships. As you read the assignment, ask yourself if a similar experience of overcoming adversity or a story of a lesson learned from one of your parents might serve as the subject of your literacy narrative.

Now It’s My Turn

So a former banker, a bassist, a rock guitarist, and a drummer walk into a bar. What are they doing? The answer: playing a show. These four men, by the names of Kevin Galloway, Hal Vorpahl, Mike Carpenter, and Jason Armstrong made up the band “Uncle Lucius” . Formed in 2005, then retiring in 2017, “Uncle Lucius” embraced the Texan music culture, inspired by musicians such as Willie Nelson. The song that helped the group gain traction, “Keep The Wolves Away”, is a true story based on the life of lead singer Kevin Galloway and his father’s misfortunes. Galloway’s father was involved in a chemical accident while at work, and being the only one working in the house, his father had to “Keep The Wolves Away” while his family struggled.

“Keep The Wolves Away” is a song about misfortune and overcoming misfortune. I feel that although not everyone’s fathers get into chemical accidents, everyone faces adversity and misfortune at some point or another, and everyone also has a metaphorical father, being someone to ward off the sorrows of life. Galloway details the way life goes on, and now that his father is growing old, Kevin is now the one “Keeping The Wolves Away” from his father. This is a song I can listen to with my best friends, or my own father, and it sparks conversation starting with “ Do you remember when…”. Yip Harburg said it best, “Words make you think. Music makes you feel. A song makes you feel a thought” .

Notes on YGT: “Now It’s My Turn”

- The writer draws readers into the first paragraph with a guy-walks-into-a-bar set-up, which he uses to introduce the band Uncle Lucius, whose song “Keep the Wolves Away” serves as his subject.

- In the summary, the writer conveys a sense of Uncle Lucius’s sound by including the group’s locale (Texas) and one of its influences (Willie Nelson).

- In the fourth sentence, “by the names of” is an empty phrase, which A Writer’s Reference defines as one that “can be cut with little or no loss of meaning” (151). Listing the names alone suffices.

- In the fifth sentence, the writer states that the group retired. More accurately, the group disbanded. At least one of its members, frontman Kevin Galloway, continues to record and perform.

- Not everyone’s father falls victim to a chemical accident. That is a statement of fact, not a perception. “I feel that” should be deleted from the second sentence of the second paragraph.

- Yip Harburg should be identified as a lyricist and the source of his observations should be listed in a works cited entry.

- As a guide for addressing trouble spots, the writer should consult these pages of A Writer’s Reference: 164-65 (exact language), 281 (periods and commas–placement inside quotation marks), and 383 (documenting sources).